Clodagh Finn: The Irish woman who made ‘Cabaret’ a hit in Ireland long before the Broadway musical

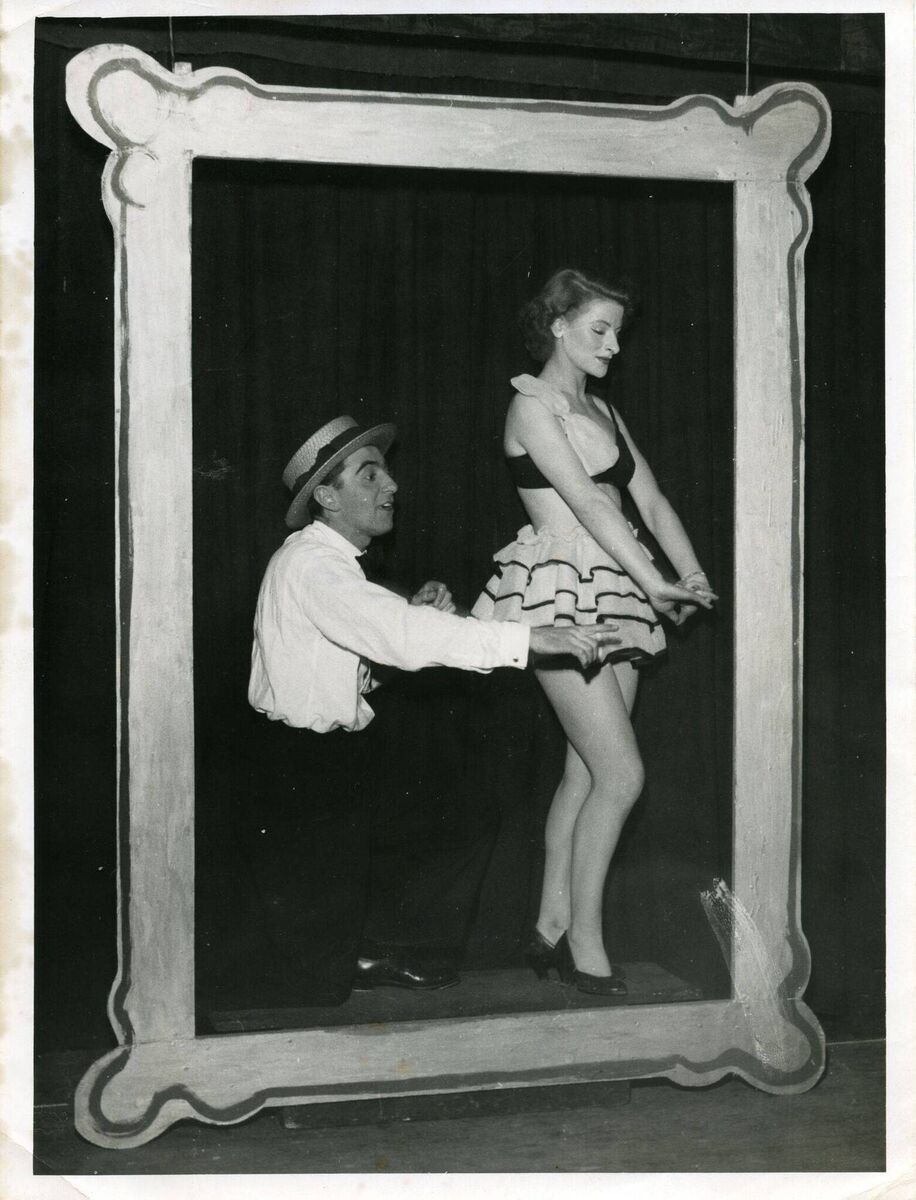

Genevieve (second from right) in 1955 with fellow cast and members of the theatre company she co-founded, The Dublin Globe Theatre. Picture courtesy of the Genevieve Lyons Archive, University College Galway Library

I was gobsmacked to discover this: In 1950s Ireland, there was a run on Sally Bowles berets after a precursor of the Broadway hit drew thousands of theatre-goers to a small but progressive theatre in Dublin.

Genevieve Lyons played Sally, the “bad girl with a heart of gold”, later made famous by Liza Minnelli, in John Van Druten’s play, . It was so successful that upwards of 15,000 people travelled from Dublin city centre to Dun Laoghaire in the suburbs to see it.

The film version, starring Julie Harris, was being screened at the same time, and many people went to both during a three-month run from August to October 1956.

The shows even sparked a trend for Sally Bowles berets, which were on sale in Arnotts and Kellett’s clothes shop. There were newspaper ads, one with a photo of a bereted Genevieve Lyons, telling the fashionable young women of Ireland that they too could be like Sally Bowles.

HISTORY HUB

If you are interested in this article then no doubt you will enjoy exploring the various history collections and content in our history hub. Check it out HERE and happy reading

It seems incredible now that a play about an extravagant cabaret singer in the louche world of pre-war Berlin, not to mention a craze to dress like her, pushed through the conservatism of a country that was banning books and plays.

Indeed, Genevieve Lyons was the female lead in the stage version of by JP Donleavy when it was closed down by Archbishop John Charles McQuaid in 1959 after just three nights in the Olympia Theatre.

Lyons and her fellow actors picketed the theatre, angry but also bemused that the “equally immoral” Sally Bowles had been given free rein a few years earlier.

And just how immoral was spelled out in one review: “Morally, she is a juvenile delinquent who never should have been allowed out of her native England by her well-to-do parents. But here she is, all rules broken in decadent Berlin; she has gone to the bad and is unable or unwilling to find the way back to decent living.”

The reviewer loved it, though, and at year-end the play was described as the highlight of 1956.

Why didn’t the archbishop shut this production down? When Genevieve and her fellow performers wrote to ask him, he simply said it was because Sally Bowles was not Irish.

An account of that exchange is published in a cleverly headlined piece, “What the archbishop said to the actress”, which ran in the in 1986.

By then, the winds of change had swept away enough taboos to allow not just a cheeky pun but an interview with a woman who spoke openly about her own marriage breakdown, her financial struggles as a single parent in London, and how writing books helped her to get out of it.

She was back in Ireland, aged 58, to promote her latest historical novel, , which proved a success despite being turned down by 13 publishers.

On an aside, the name was due to Princess Margaret, sister to Britain's late Queen Elizabeth II. Genevieve had unexpectedly found herself at dinner with the royal. When the princess asked her what she planned to call her book, a multi-generational saga about an Irish family that starts with the Great Famine, she said: “The Survivors.”

“Eah,” said Ma’am, “Is it about a lot of people on a rawft?” When she said it wasn’t, the princess insisted that she couldn’t call it that, hence the title . That nugget comes from a delightful piece by Maire Crowe in the .

It is both inspiring and moving to read the press coverage that accompanied her 1986 book launch. Here was a middle-aged Irish woman on her fourth career, talking about moving to London, getting work in TV shows like and , separating from her husband Godfrey Quigley, and then falling on very hard times as a single parent to her daughter Michele.

“It happened twice in my life,” she told Siobhan Crozier in the “God just puts his arm out and wipes the table completely clear and everything gets smashed in the process, but if you can survive it, you suddenly find that the alternatives are terrific.”

That survival instinct comes through very strongly in an interview with Mary Kenny. After Genevieve lost her teaching job in London during Christmas week, she was distraught. And totally broke.

Kenny writes: “She knelt down and prayed for the means to buy Michele a Christmas present. As she was praying she noticed a greasy stain on the carpet. It occurred to her that she should move the carpet around, so that the stain would not show. When moving the rug she found four 10-pound notes underneath it.”

“That sort of thing is always happening to me. I am at my wits’ end and suddenly… providence steps in,” Genevieve said.

Her writing career (20-plus books) did not make her rich, but it kept her and her daughter afloat and allowed them to travel all over the world, albeit on a shoestring.

Here’s one wonderful description of her adventures: “I’m a lunatic traveller. I’ve travelled 900 miles across the Sahara desert by camel and jeep, and I’ve done a walking tour of the Carpathian mountains where the monks are the randiest men in the world.”

By any standards, Genevieve Lyons’ life and work were extraordinary yet, as so often happens, it faded from memory.

Time moves on, of course. That is a given, but why was her work, particularly as one of the few female co-founders of a theatre company, not included in the histories of the stage that have been written since?

That was a question Barry Houlihan, University of Galway archivist, asked himself when he came across her quite by accident while researching .

It was a revelation, he says, because her work debunked the traditional image of 1950s Ireland. Rigid social standards might have been firmly in place, but there was also a generation of theatre-makers, men and women, who fuelled a vibrant cultural resurgence.

He says:

He was considering how to research and record that work when Michele McCrillis, Genevieve’s only child, got in touch to ask if the university would be interested in her archive. Providence stepped in, as Genevieve herself might have said.

The archive is a treasure trove of reviews, press clippings, programmes, prompt books and photographs, including one of Genevieve Lyons as Sally Bowles, complete with beret and elegant cigarette holder held high.

She was the shining star of Dublin in the 1950s, but she was also an innovator. She co-founded the Globe Theatre Company, an ambitious project that brought international work to an audience outside of Dublin.

Her diaries also offer a new perspective on the social record of Ireland. As a woman in her 20s, Genevieve was working in the bank by day while pursuing a frowned-upon artistic career outside of that. There were times when she would go to the theatre, the pictures and the dance hall all in one evening.

Her life, work and legacy are preserved now but their fortuitous collection raises a bigger question, says Barry Houlihan: “Why are the archives of really significant Irish cultural figures who are women not as common within our libraries and archives as those of male figures?

“And why are such archives not being brought forward by many descendants and families to be preserved in the first place? Over recent years I often saw such archives of Irish women, all but forgotten, in family attics and sheds.”

Some of those stories have been retrieved and their archives preserved — too often by accident, as Houlihan outlines in an eye-opening talk organised by The Royal Irish Academy. A more recent updated version will be released online by the Archives and Records Association soon. Keep an eye out for it.

In the meantime, look through those dusty boxes under the stairs to see what undiscovered threads of our national story are hiding within.