Terry Prone: Hemingway's cocktail of brain chemicals and concussion could have been dementia

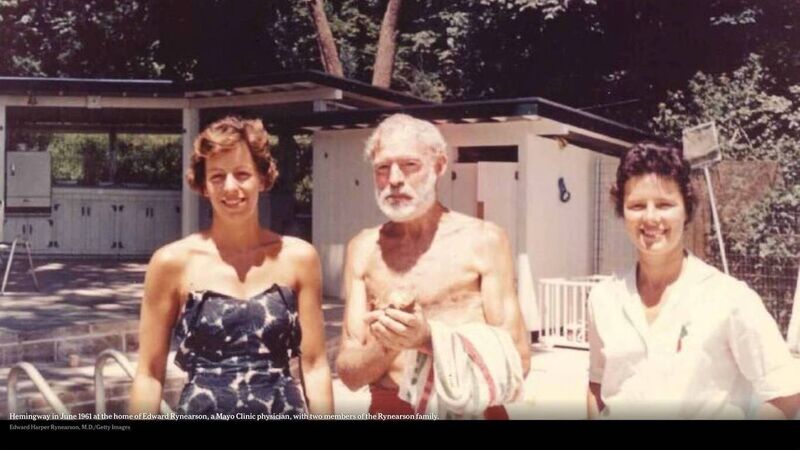

Ernest Hemingway in June 1961 at the home of a Mayo Clinic doctor with two members of the doctor's family. He hardly exists and — at 61 years of age — looks so fragile and shrunken, he could be two decades older.

Two photographs, taken only a few years apart, of ostensibly the same man: Ernest Hemingway. Impelling, the story their contrast tells.