Clodagh Finn: If only we had hospital builder Madam Steevens in today's world

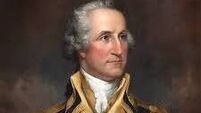

From a portrait of hospital builder and philanthropist Grizelda Steevens by Michael Mitchell. Picture: By permission of the Trustees of the Edward Worth Library © The Edward Worth Library.

Every time I hear of another delay to the opening of the children’s hospital — the 16th at last count — I wonder what the indefatigable Grizelda Steevens would make of it.