Sarah Harte: Anxious generation needs to be faced with academic challenge of Leaving Cert

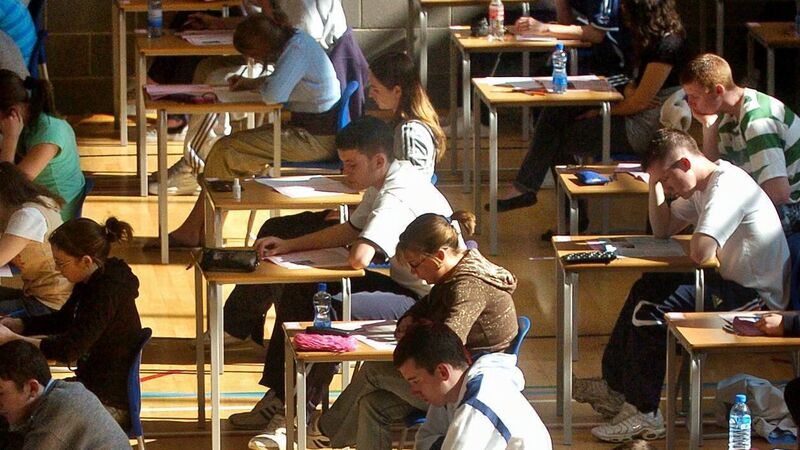

The Leaving Cert should not be dumbed down. File picture: Denis Minihane

Young Irish women are highly anxious — hardly a surprise when we live in an age of anxiety. One of the hit songs of the moment is , an anthem describing 'an elephant sitting on my chest', by the rapper Doechii, a young woman who appears to have captured the zeitgeist.

Last week, a charity called The Shona Project published the results of their national survey capturing the views of young women. Naturally, the results revealed widespread anxiety and pressure. The Shona Project helps young Irish girls navigate the challenges of growing up by providing practical advice, fostering a sense of solidarity, and encouraging them to be their best selves.