Clodagh Finn: The Irish nun whose ‘escape’ divided Australia

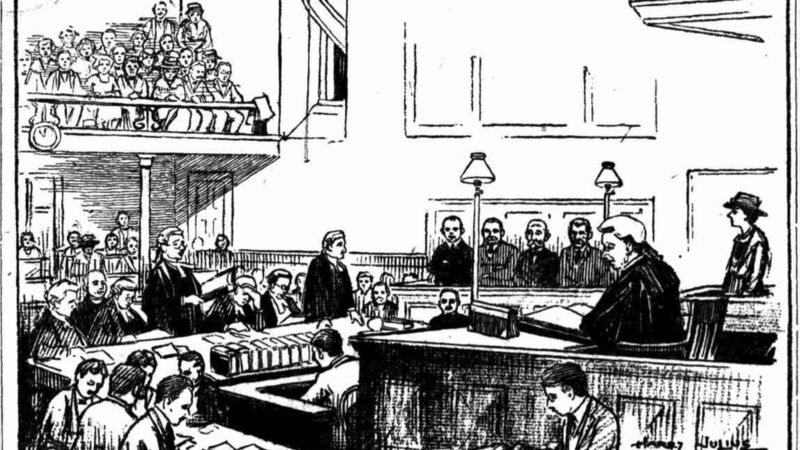

An illustration from the Supreme Court case taken against a bishop, claiming damages for falsely and maliciously procuring the arrest and imprisonment of Bridget Partridge. Pictures: courtesy of Jeff Kildea