Paul Hosford: Is it too easy to get on the ballot paper in Ireland?

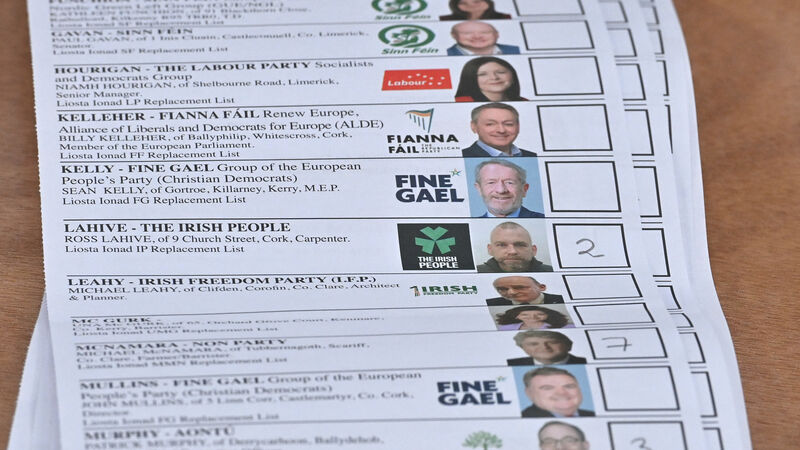

To be included in the European elections last week, you had to fulfil one of three criteria: be nominated by a registered political party, pay a deposit of €1,800 or obtain 60 signatures supporting your nomination from the public. Picture: Dan Linehan

If you've never been to a European election count, it's an incredible operation.

In Cork this week on top of a plastic floor that conducted static electricity so well that it turned every handshake or contact with the guard rail into a minor shock, dozens of staff drafted in for the week worked through 713,000 ballots for five full days.