Joyce Fegan: Action needed over petty wars of words in housing

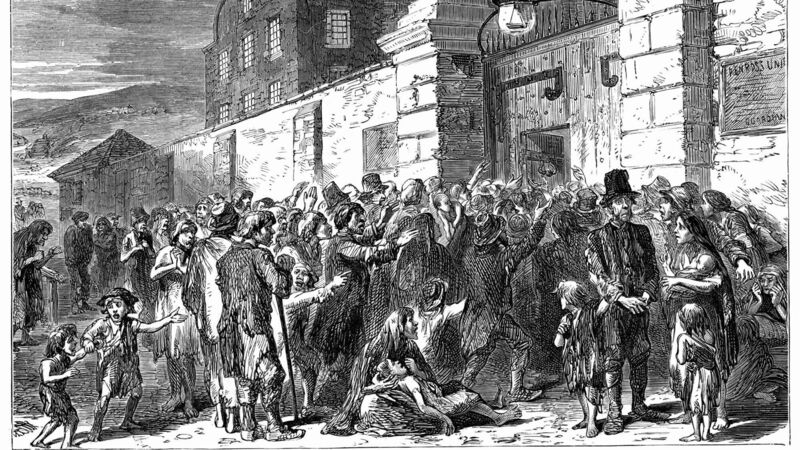

Illustration of Famine victims at a workhouse gate from "The life and times of Queen Victoria" by Robert Wilson (1900). It is estimated that between 250,000 and 500,000 Irish families were evicted from their homes during the Famine years. Photo: The Print Collector/Getty Images

"The fact is a fiction," said the late playwright Brian Friel. He was referring to memory, and how it might not be the most accurate of historical representations, but still, it holds a reckonable force, a truth, of some kind.

If you take a left out of Delphi Resort, that almost rite-of-passage Irish childhood destination in Connemara, you'll follow the road until you arrive at one of those Wild Atlantic Way signs. It is the Doolough Valley Famine Memorial, remembering the 400 men, women and children who walked from Louisburgh to Doolough in the spring of 1847, in search of food and tickets to a workhouse. Both desires were refused. And so, in very bad weather, they attempted to return to where they had come from. Many perished on the journey back.

At the height of the first lockdown in April 2020, the poem Quarantine by Eavan Boland, went viral online. Its title just happened to coincide with the times, but the poem itself was being widely shared because the Stanford professor had just died.

"In the worst hour of the worst season, of the worst year of a whole people, a man set out from the workhouse with his wife," begins the poem. The man ends up carrying his wife as she is too sick with "famine fever" to walk. They arrived at their new unnamed destination in the bitter cold of night, but in the morning both were found dead.

"Of cold. Of hunger. Of the toxins of a whole history. But her feet were held against his breastbone. The last heat of his flesh was his last gift to her. Let no love poem ever come to this threshold," wrote Boland, setting her poem in the winter of 1847.

In my mind I have conflated art and history, imagining this couple as part of the 400 people who travelled south towards Delphi in the early spring of 1847. But both the seasons, and the direction of travel differ even if the year and the social issue coincide.

It is estimated that between 250,000 and 500,000 Irish families were evicted from their homes during the Famine years — it is a figure widely debated, according to Dr Ciarán Reilly, historian of 19th- and 20th-century Irish history at Maynooth University.

And actual evictions in the mid-1800s didn’t follow a neat, straight line from the potato blight, but instead were often preceded by legislation. According to Dr Reilly, the evictions of the mid-1800s came in four waves.

There was firstly the Irish Poor Law Act of 1838 — this is when people were essentially evicted into workhouses and poorhouses.

The second wave was different in that it came not after legislation, but after the 1841 General Election. Dr Reilly said "landlords reacted to their waning political influence by evicting tenants".

The third tranche of evictions came after the Gregory Act of 1847, and the final wave came after an 1849 piece of legislation called the Encumbered Estates' Court. This Act legislated for the eviction of people before and after the sale of an estate.

According to our National Archives, the poorhouses were originally intended to house 1% of Ireland's population. But by March 1851, approximately 320,000 people were housed in the system.

In early March of this year, the Irish Government decided that the current ban on evictions would not be extended past March 31. It is a decision that has been met with ferocious reaction and rhetoric, but mostly by those who will not be living out the consequences of such a decision.

The eviction ban was something that was part of emergency measures introduced during the pandemic, and yet, it was an idea that Fr Peter McVerry tabled several years ago.

Six years ago he said: “It should be made illegal to evict people into homelessness, particularly families. That’s what we did during the Famine years and we’re still doing it today in 2017."

The line caught headlines, naturally because he mentioned evictions and the Famine in the same sentence, but few took real notice, and certainly no one took action.

Speaking in 2019, he had this to say: "Homelessness now has become normalised.

In that same interview he referred back to 2012, a time in Irish society when "there was no such thing as homeless families in our society, they didn't exist". It's some trajectory, to go from no homeless families in 2012, to where we now find ourselves in 2023.

Latest figures from the Department of Housing show that there are 11,754 people homeless in Ireland, including 3,431 children. This is the highest number of homeless people on record, since records began in 2014.

Add to these figures, those from the Residential Tenancies Board (RTB), which show that 7,348 households have eviction dates looming in the coming weeks and months.

We've heard every excuse under the sun over the last decade: there wasn't the money to build; there was the aftermath of the housing crash to contend with; we were over-relying on the private rental sector; you can't control a private market; modular homes couldn't be built fast enough; there's no point pumping money into restoring derelict or damaged properties, and on and on and on.

And there were as many solutions tabled as there were excuses: let's return to homes above shops; the Land Development Agency; rent freeze zones; returning derelict properties to use; mixed funding for big builds with some funds coming from the corporate sector; mortgage-to-rent schemes to address those in arrears facing homelessness and the not-for-profit cost-rental model — where your rent covers the cost of construction, management, and maintenance of your securely-tenured home.

In 2019, this is what Donal McManus, CEO of the Irish Council for Social Housing (ICSH) had to say: "Between 2010 and 2016, 300,000 social homes were not built. If they had been built it would have freed up space in the private rental sector."

So in 2023, each and every one of these backlog of problems have caught up on us, especially after a pandemic-induced eviction ban.

But while this area might just be figures, and figures of speech to some, there are mothers and fathers who tile people's kitchens and clean people's homes who are facing evictions, having never earned enough to be able to qualify for a mortgage, but who have been paying tax and contributing to our society for decades.

And what's so disappointing at this juncture is that we have some politicians using precious minutes in Leinster House to debate who cares the most, people with platforms attacking others for their artistic interpretation of today's events, and rows are breaking out over who said what, instead of a laser-sharp focus on implementing the practical solutions we've had to hand all these years.

The only solution is to turn rhetoric into results, and to put an end to this normalisation of homelessness as an inevitable social issue.