Sarah Harte: Sanitising literature serves to cover up critiques of hateful attitudes

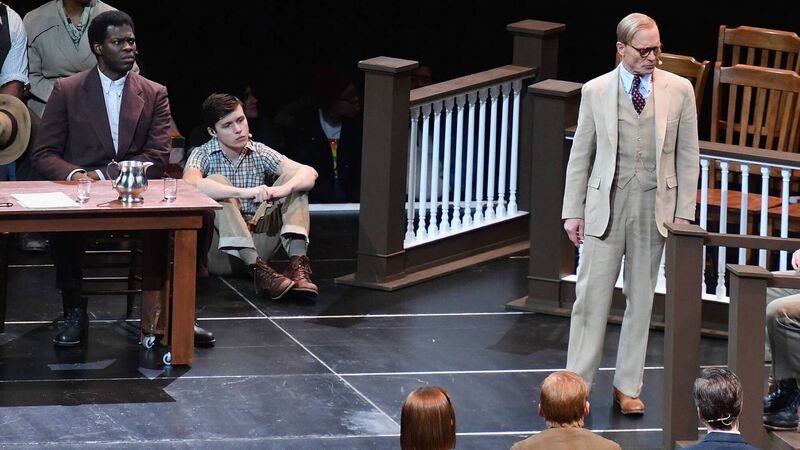

A scene in the Broadway production of Harper Lee's , by Aaron Sorkin. Sorkin is widely regarded as a master storyteller, but has been critiqued for his liberal 'tendency to write around facts that contradict his overall argument' so 'he can come out on the right side of history'. Picture: Angela Weiss/AFP/Getty