Michael Moynihan: We need an app to create a fragrant trip through Cork’s streets

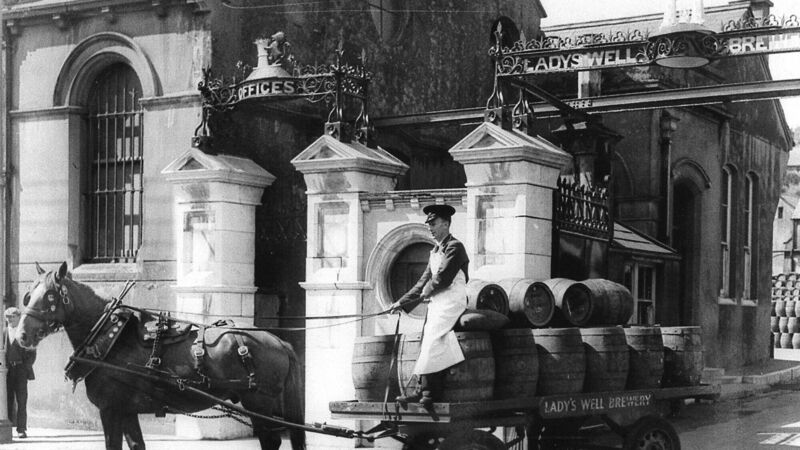

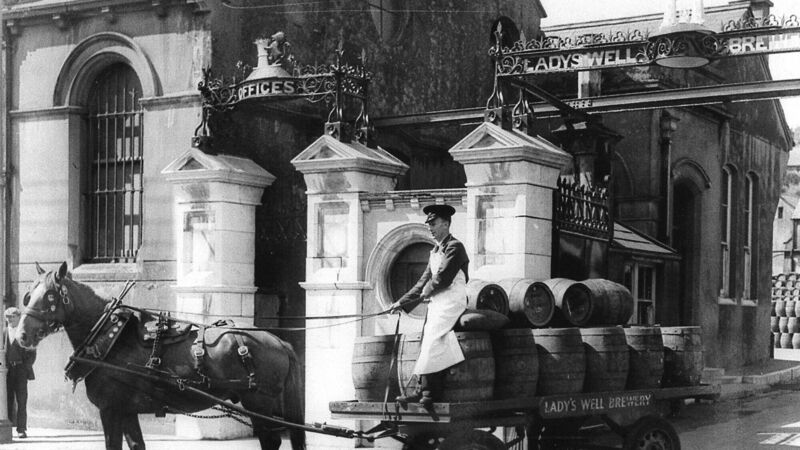

A horse and cart crossing Patrick's Bridge to deliver barrels of Murphy's stout to a pub in Cork city in the early part of the last century

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBE

A horse and cart crossing Patrick's Bridge to deliver barrels of Murphy's stout to a pub in Cork city in the early part of the last century

A few months ago I wrote here about a smell in Cork so pervasive it seemed to pursue me everywhere, curling its way in under doors, gathering in an unseen cloud to besiege me at bus stops and shop entrances.

It was the smell of weed, and when I raised a light objection to its ubiquity in the city the online reaction was ... suffice to say it rather undercut the idea that smoking the substance has a relaxing effect on its users.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.

Select your favourite newsletters and get the best of Irish Examiner delivered to your inbox

Monday, February 9, 2026 - 5:00 PM

Monday, February 9, 2026 - 7:00 PM

Monday, February 9, 2026 - 8:00 PM

© Examiner Echo Group Limited