Clodagh Finn: Meet Mairin Mitchell — honoured abroad but unknown at home

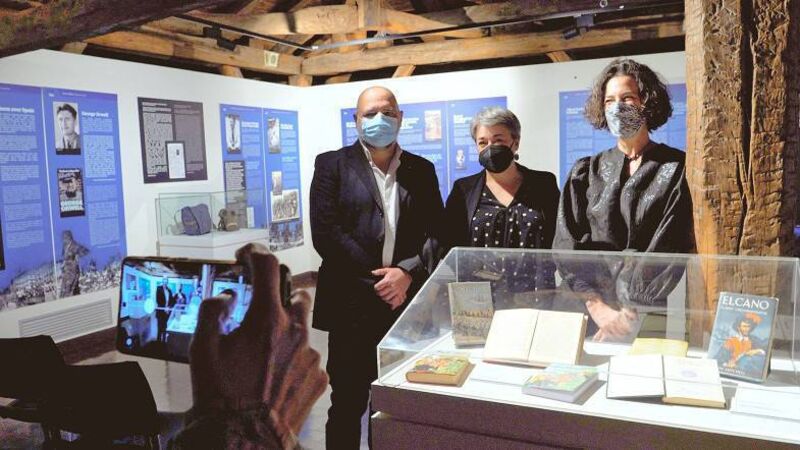

Xabier Armendariz, curator of the Mairin Mitchell exhibition, which was organised by the Biscay provincial council; Euskal Herria Museum head Leire Irazabal; and Basque language, culture, and sports deputy Lorea Bilbao Ibarra.