Clodagh Finn: We could all learn a lot from the astonishing story of Albert Cashier

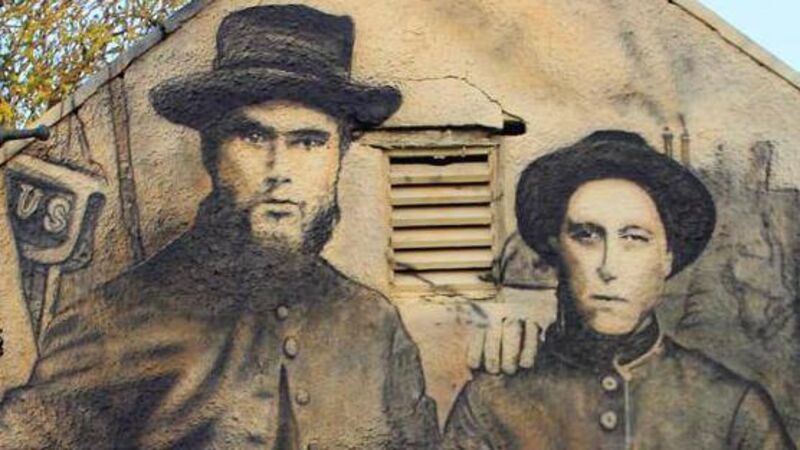

The mural by Ciarán Dunlevy commemorates Albert Cashier from Clogherhead Co Louth who fought in the American Civil War. Picture: Ciarán Dunlevy

The story of Albert Cashier of Clogherhead in Co Louth is a story for our times, for so many reasons. A spectacular mural showing him in uniform alongside a fellow soldier reminds us that some 200,000 Irish people fought in the American Civil War.