Clodagh Finn: Why we need to make empathy a mandatory subject in schools

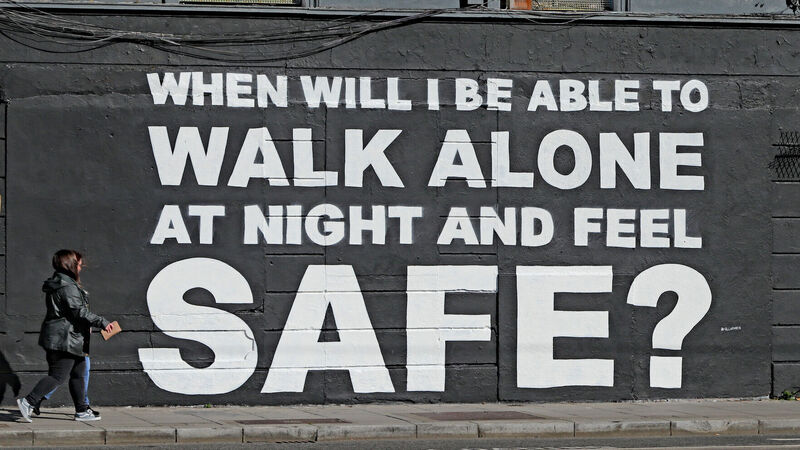

A member of the public walks past the latest mural by Irish artist Emmalene Blake in Dublin's city centre. Picture: Niall Carson/PA Wire

There was a day last week when I had to turn everything off — the TV, the radio and the push notifications that push (they are appropriately named) the violent outside into your inside pocket, which is where I keep my smartphone.

Pocket atrocities, I call them not just because that is where they are delivered, but because the rolling headlines make reports of individual misery so banal that they are somehow rendered pocket-sized. Small, forgotten news briefs in an ever-moving cycle.