Joyce Fegan: Reject the fallacies, fearmongering, and scolding of Ireland's austerity fans

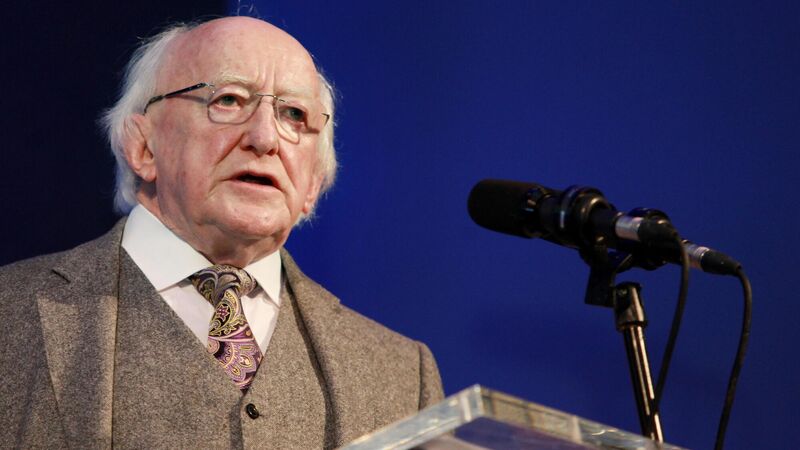

Speaking to Pat Kenny on Newstalk in 2020, President Michael D Higgins advocated 'universal basic services ... a floor of basic services that will be there to protect us in the future'. File photo: Leah Farrell/RollingNews

People have died alone. Women have laboured in car parks in the dead of night, just so they wouldn’t have to leave their partners. Cancer patients were dropped off at hospital doors, to be picked up at the same spot after treatment.