Clodagh Finn: We must help bookshops weather Covid storm

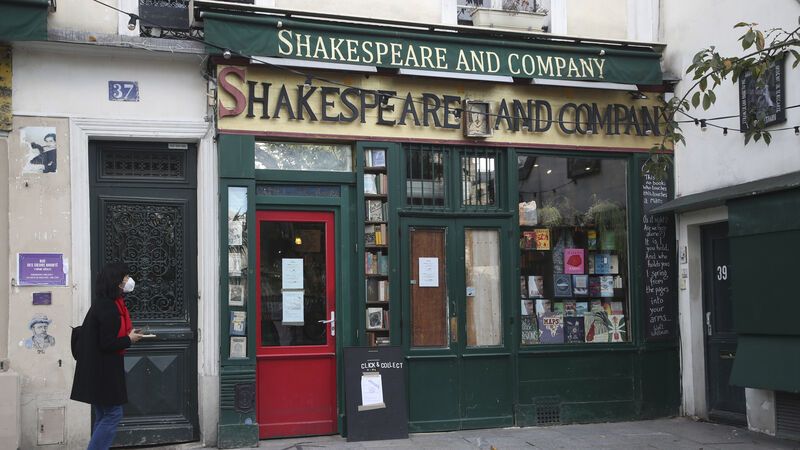

Legendary bookshop Shakespeare and Company in Paris hit hard times during the pandemic. Picture: AP Photo/Michel Euler

How I miss bookshops and everything about them. The browsing, the floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, the heady smell of paper. There’s certainly a case to be made to have them classified as essential businesses, even in these Covid-challenged times. To borrow a phrase from Liverpool manager Jürgen Klopp, they are the most important of the least important things.

They are always the first places I seek out whenever I visit a new town or city. They help me find my bearings, a sort of zero-mile marker from which to measure all forays to the shops. Perhaps that’s why news of hard times at Shakespeare and Company, the world-famous bookshop which is a stone’s throw from the real ‘kilometre zero’ in central Paris, struck a particular chord.