Michael Clifford: Who wouldn't want to die with dignity?

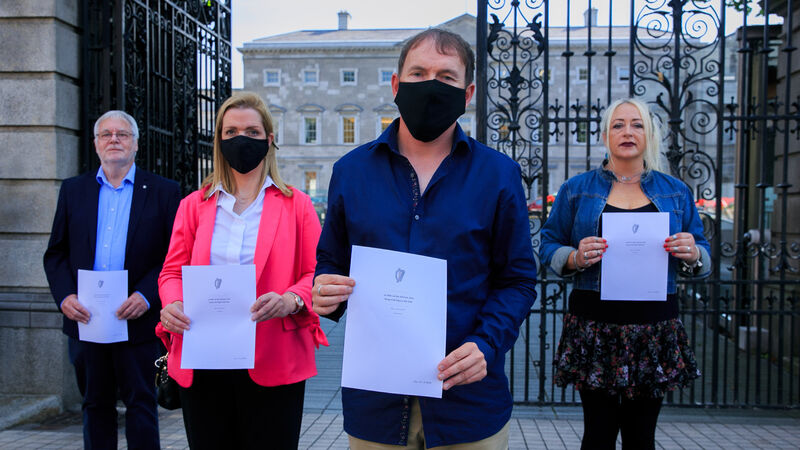

Tom Curran, Vicky Phelan Gino Kenny, and Gail O’Rorke at the launch of Dying with Dignity bill. In 2015, Ms O'Rorke went on trial, charged with assist her friend Bernadette Forde to take her own life. She had acted out of love and was found not guilty. Picture: Gareth Chaney/Collins

Who wouldn’t want to die with dignity? Who would want to devalue living with a disability or the capacity to find reason or contentment as the light fades?

Those are the big questions in the debate that must follow the introduction of a Dying with Dignity bill this week. The bill was presented to the Dáil by People Before Profit TD Gino Kenny on Thursday. It proposes strict conditions in a law to allow a person take their own life if suffering from a terminal condition.