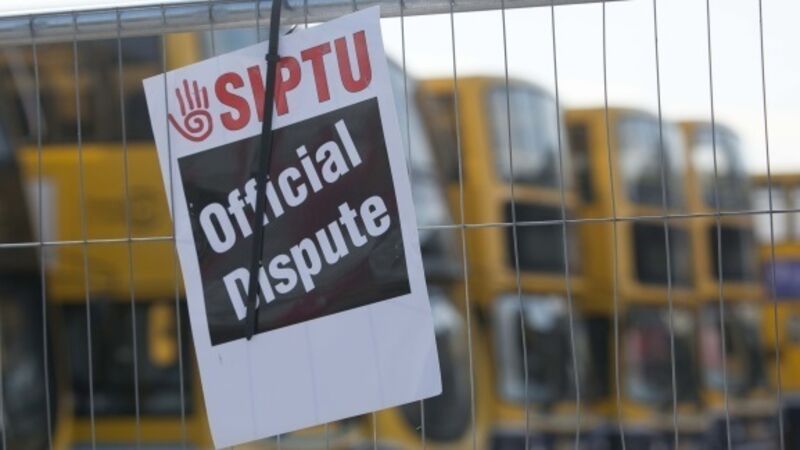

New national agreement needed to stave off a winter of discontent

SO, are we looking at a winter of discontent? Or are we anticipating a government desperate to stay in office and willing to make any concession necessary to stave off division in its own ranks?

Either is possible. There is no doubt that throughout the public service (and beyond) there’s a lot of pent-up anger and frustration about pay cuts that people have endured for seven years now. It started before the Troika arrived, when Brian Lenihan told the Dáil that “we are now fighting for the economic future of our country”. He blamed the global financial crisis, which he described as the worst in 70 years, as having a profound effect on our banking and financial sector.