When playing the blame game never blame it on the obvious

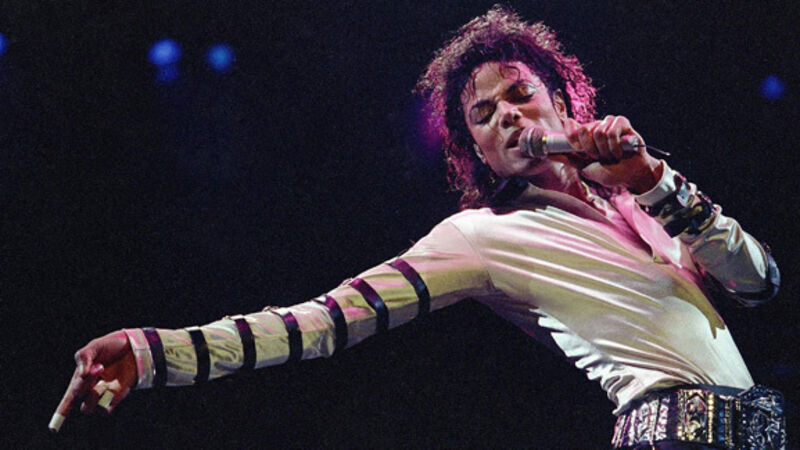

It was singer Michael Jackson who best-articulated the conundrum of blame, when he tried to figure out why he wasn’t ‘getting no loving’ nor able to control his dancing feet.

While others in his circle were quick to blame the sunshine, the moonlight and good times, this was not good enough for the perfectionist king of pop.