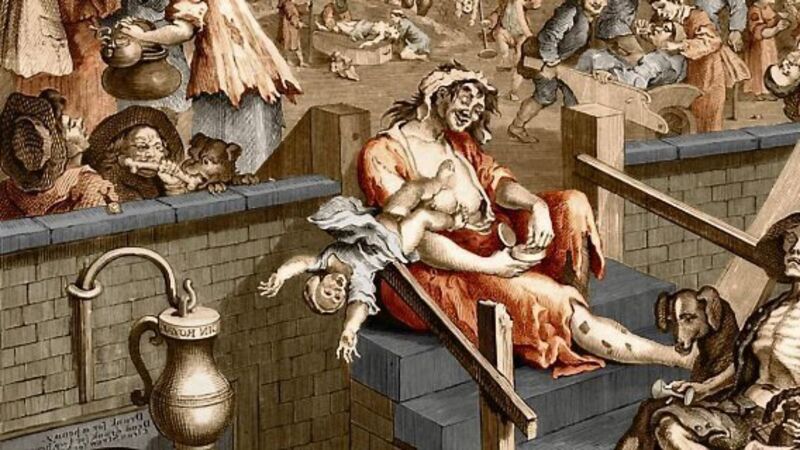

Gin Lane’s alcoholic miseries are still to be seen on streets of Ireland

Hogarth cheaply sold prints of the cartoon, because he wanted the ‘movers and shakers’ of his time to understand what was happening, and his pal, writer Henry Fielding, supported him.

“In Gin Lane,” Hogarth said, “every circumstance of [gin’s] horrid effects is brought to view...Idleness, poverty, misery, and distress — which drives even to madness and death — are the only objects that are to be seen, and not a house in tolerable condition, but the pawnbroker’s and gin-shop.”