An ill wind: How Storm Éowyn uncovered ancient Irish burial sites after 1,300 years

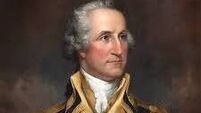

An aerial view of St Manchan's church at the ancient monastic site at Lemanaghan, Co Offaly. Picture: Annie Holland

The timing would give you pause for thought.

When Storm Éowyn ripped through the ancient monastic site at the Lemanaghan bog in Offaly last year, it uprooted four mature trees, exposing a number of previously-unknown early medieval burials enmeshed in their root-balls.

Check out the Irish Examiner's WEATHER CENTRE for regularly updated short and long range forecasts wherever you are.