Disinformation, the electoral register, abuse of politicians: The issues facing the Electoral Commission

Art O'Leary, CEO of the Electoral Commission, expects we will see significantly more fake videos like the one of then-presidential candidate Catherine Connolly when it comes to election time. Photo: Moya Nolan

It looks like a clip RTÉ News would routinely share on its social media channels. It starts with what looks like veteran broadcaster Sharon Ní Bheoláin before cutting to then-presidential candidate Catherine Connolly.

“In the last few minutes, at a Catherine Connolly campaign event, Catherine Connolly has confirmed her withdrawal from the presidential race,” Ms Ní Bheoláin says.

And then Ms Connolly takes it up: “It is with regret that I announce the withdrawal of my candidacy and the ending of my campaign.”

The clip is then taken up with political correspondent Paul Cunningham outside Leinster House, who declares “simply put, Friday’s election is now cancelled, it will no longer take place... as for Heather Humphreys, she will become the winner automatically and will be appointed tomorrow”.

For the man in charge of the integrity of Ireland’s elections, this obviously fake but also believable-looking video made with artificial intelligence set off a slew of alarm bells as it began to be shared widely on social media just days before the presidential election.

Art O’Leary, the chief executive of Ireland’s electoral commission An Coimisiún Toghcháin, said it was the kind of thing he had been watching out for throughout the campaign.

“During presidential elections, our radars and our antenna are very finely tuned, very finely sharpened,” he told the . “We're always on the lookout for issues as they arise.

“It's the first time we had seen a sophisticated, deep fake. You know, most of the efforts up to now have been ham-fisted or amusing. If there was going to be something emerging, it tends to happen in the last few days before polling day, because there isn't much time to go and get a counter-narrative out there or to debunk it as well.”

Mr O’Leary said one of his colleagues spotted it late on the Tuesday before polling day, and they made the call to take immediate action.

He said: “We do have what the social media companies call whitelist channels, which gives us priority access to report issues, and Meta, in this particular case, were very responsive.

While the video was quickly taken down by Meta, it wasn’t before thousands had already seen the video with the electoral commission boss likening it to “whack a mole” trying to stop the spread of such content.

And then there are the social media companies too, which Mr O’Leary said “maybe won’t be as co-operative” in other instances when bodies such as his reach out.

Going forward, he expects we will see significantly more fake videos like this when it comes to election time, and he sees his job as educating the public so they won’t be duped when they come across it.

“It’s inevitable,” he said. “The potential here is off the charts. You know, I speak to my counterparts all the time, all over the world, and it's the one thing that we come back to. At the top of every agenda is misinformation and disinformation, deep fakes and and how we manage that.

“Ultimately, the long-term solution here is digital and media literacy. We need to educate people in relation to the material that they find online.

“It is possible, with an army of chatbots that we simply become overwhelmed. And that’s where the difficulty is with trying to regulate or hold the social media companies to account. Because if thousands of these things are appearing in minutes or hours, it’s trying to keep track of all of them.”

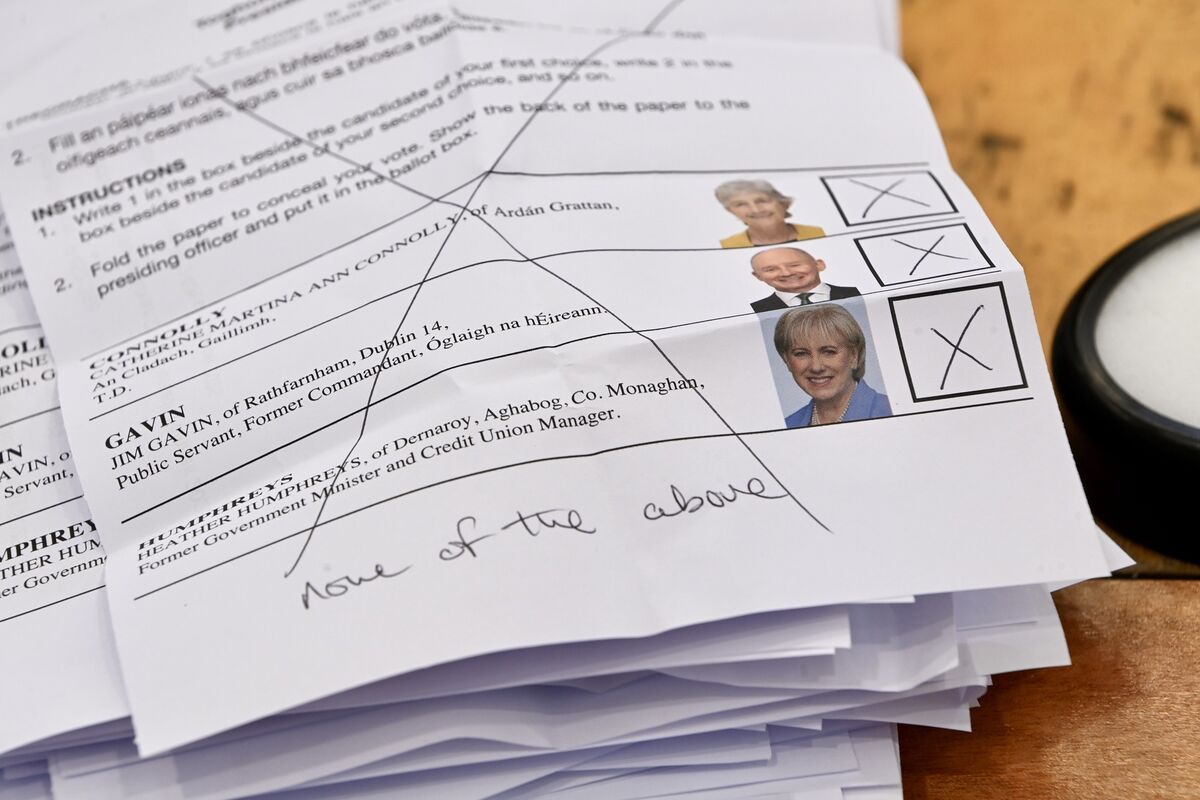

Another key feature that emerged from the recent presidential election was the “spoil the vote” campaign.

A disparate group of figures led the charge calling for voters to spoil their vote, from right-wing, anti-immigration individuals with large online followings to anti-establishment figures.

More than 200,000 people spoiled their vote, almost 13% of all votes, while a further 100,000 voted for Jim Gavin even though he had withdrawn from the campaign many weeks before.

A key part of the dissatisfaction being spread online was that barrister Maria Steen didn’t get on the ballot paper.

Ms Steen, a member of the Iona Institute who has in the past represented the body in campaigns for no votes in the Eighth Amendment referendum and the marriage equality referendum, failed to secure the support of enough members of the Oireachtas to secure a nomination to contest the presidential election.

Mr O’Leary said a report they are expecting in the new year will reveal more about the motivations behind spoiling their vote, but he stressed that “any person has the right to spoil their vote”.

“I know there are many people who felt that they would have liked an additional candidate on the ballot paper,” he said. “And presidential elections are the only election where we make it hard for somebody to get on the ballot paper.

“I saw thousands of spoiled votes. I was in a number of count centres on on the count day, on the 25th of October. And I saw Maria Steen's name. I saw Paul Mescal's name, Conor McGregor's name. ‘None of the above’, ‘you’re all corrupt’.

“There are lots and lots of different reasons, and our data might provide some evidence in relation to what that might have meant.”

Mr O’Leary also hit out at the “illegal” posting online by people who had spoiled their ballot papers.

“People are not supposed to take photographs of ballot papers, and because the privacy of the vote, and it's supposed to be very personal to you etc, so it's a secret ballot,” he said. “It's not something we encourage.”

Going forward, the kinds of abuse those in politics, or those hoping to enter it, face is also a concern for Mr O’Leary. In 2024, a task force set up by the Oireachtas on “safe participation in public life” concluded that “abuse in political life is prevalent, problematic and targeted disproportionately at women and minority groups”.

It added: “Online abuse is intensifying and becoming normalised, fuelled by the anonymity provided by digital platforms, and often driven by misogyny, sexism, racism and intolerance.”

This autumn, the Houses of the Oireachtas Service said it would look to improve security at Leinster House in the years to come amid safety fears, with Ceann Comhairle Verona Murphy calling for legislative proposals to defend political debate from an “alarming rise in serious threats” against elected representatives.

While it is set to make recommendations to Government in the new year on whether to retain election posters that feature on poles all around the country at election time, Mr O’Leary said such posters can be a safer way of letting the electorate know about a candidate.

“In an environment where increasingly door-to-door canvassing is becoming more problematic, particularly for women and particularly for young people as well. Some of the dangers that have been described by that Oireachtas group on public safety, that harassment, intimidation, physical threats,” he said.

“Maybe posters are a way of counteracting that, it's another way of people to become a little more visible. I don't want to give a view, because I don't want to pre-empt what the recommendations might be, except to say that clearly that posters are damaging to the environment.”

One of the main frailties of our electoral system is one that has already been lain bare by Mr O’Leary and his organisation, namely the mess that is the electoral register. There is currently no single electoral register in Ireland. Rather, there are 31 for each local authority.

People who are dead, have moved abroad and duplicates where people are registered both where they now live and where they used to live — there are estimates that hundreds of thousands of names are on there that shouldn’t be.

“[We are] deeply concerned about the levels of accuracy on the electoral registers,” the commission said in a report published last May.

To try to fix it, the Government has pumped in €3m to local authorities in 2025 to support them migrating all the data from their own electoral registers into one single register. Mr O’Leary is bullish that this problem that has been flagged for decades may finally be on the way to being fixed.

“Astonishingly, this is an IT project in the public service which is going brilliantly well and the work that the 31 local authorities have put into the register in the last 18 months or so has been nothing short of extraordinary,” he said.

“There is a brilliant project going on at the moment to create a single database, and all of the local authorities are going to migrate to that single database by this time next year. I mean, I'm skeptical at the best of times about everything, of course, because I'm a civil servant, but I've been really impressed by the energy and commitment of the local authorities.”

Fixing the electoral register will give much more accurate figures on voter turnout in the elections to come, and Mr O’Leary says a focus in 2026 will be reaching out to the sizeable portion of the Irish public who never get out to vote.

Their data shows a third of non-voters don’t make a connection with elections and decisions then taken that affect their lives, and these are a particular “target” group for the commission.

He added:

“So, this is what we're trying to say to people that there is that connection between having a voice and having it heard when it comes to some of the big decisions in Ireland.

“I'd like to think that we're starting to make inroads in this. We registered half a million people last year. But we don't necessarily make it easy for people to actually go and vote. We need to convert all these registrations into voters, and that's our big challenge.”