Mick Clifford: Why Daniel O’Connell was Ireland's greatest politician

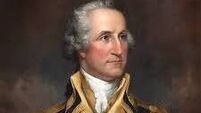

Daniel O’Connell was, during his lifetime and for maybe half a century after his death, considered in many circles to be the greatest Irishman who ever lived.

Daniel O’Connell liked to remind people that he was born in the year that America began to assert its independence. His date of birth was August 6, 1775.

America’s Independence wasn’t completed until the following July 4, but O’Connell was a good storyteller, specific with dates when needed, vague when a convenient narrative required embellishment.