Johnny Duhan: How the singer fought the law and won

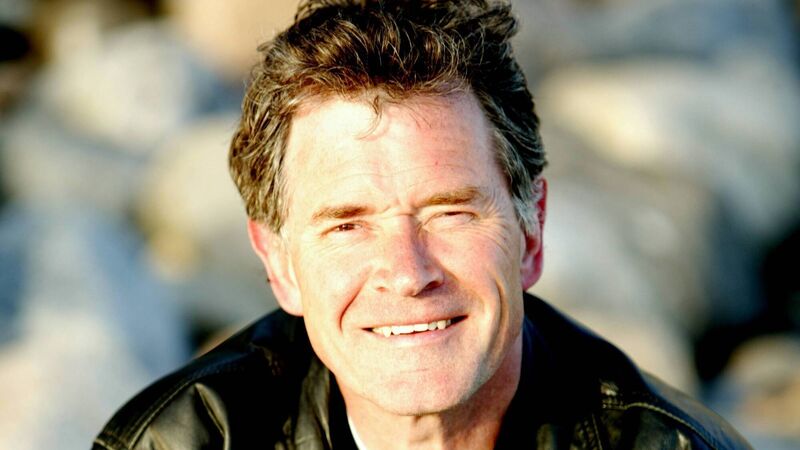

Singer/songwriter Johnny Duhan. The Limerick native, who has in Barna in Galway for many years, drowned after going for a swim at Silverstrand near his home.

The man on the phone said he was Johnny Duhan. I wouldn’t have believed it but for the voice. Even as he talked, I was transported back to the 1980s, the song on the radio, a DJ talking about this guy from Limerick, and a singing voice like a plea, full of vulnerability, as if imparting something from deep within, yearning for love of one sort or another, repelling pain.

Johnny Duhan died last Tuesday in a drowning accident off the coast of Galway. He was 74 and many tributes have since been paid to his songwriting feats. He was, as pointed out by his fellow musician Fiachna O Brainan, “a master wordsmith”. He was best known for his song ‘The Voyage’, recorded by Christy Moore and now a staple at every second wedding in the country and beyond.