The first bomb on May 17, 1974, went off in Parnell St at 5.28pm. It had been placed in a Hillman Avenger, metallic golden olive in colour. The car had been stolen that morning in Belfast.

Andy Rowan, from Cederwood Rd in North Dublin, was a teenager at the time, accompanying his father in his father’s van. Rowan is a brother of the artist Guggi.

“We stepped back into the van and the bomb exploded and blew the doors outwards,” Rowan tells the documentary film May-17-74: Anatomy of a Massacre.

“I got out [of the van] and where I got out lying at my feet was one of the men who died. A newspaper, somebody got a newspaper and covered this man with it. It just got red. My dad ran to help a lady who had both her legs blown off.”

Some 10 people died as a result of the Parnell St bomb.

The bomb on Talbot St went off at 5.30pm. The bomb car was a metallic blue Ford Escort, which had been stolen in Belfast that morning. Bernie McNally was working in O’Neill’s shoeshop on the street on the day in question.

A customer came in late and requested a pair of shoes that were not on show in the shop. Bernie went downstairs to the storeroom to get the shoes. She was down there when she heard the bomb going off in Parnell St, but she wasn’t sure whether it was a bomb at the time.

May McKenna who lived in a flat over the shoe shop also heard the Parnell St bomb go off and she came down to the shop.

She was standing near the door at 5.30pm, and Bernie was further into the shop.

“A big flash came in the sky and threw us all in,” Bernie tells the filmmakers.

“Onto the floor. I don’t know what happened. We all ended up on the floor. May McKenny was killed. The later night shopper I went to get the shoes for was dying.”

Some 14 people lost their lives in and around Talbot St on that day, as well as an unborn child whose 20-year-old mother Colette Doherty was among the dead.

The bomb on South Leinster St went off at 5.32pm. It exploded in an Austin 1800 Maxi, lagoon blue in colour. The car was owned by a taxi company in Belfast.

That morning it was hailed by a man who asked to be driven to the Sandy Row area of the city.

Three other men were picked up along the way, the car taken and the driver held until the afternoon. The car was then driven south.

Kevin O’Loughlin’s mother Christina was one of two people who died on South Leinster St. Hours after the explosion, she hadn’t come home.

“An uncle of mine and my father said it would be better going out searching, but I know they ended up going to the morgue and identified her there, and then they came back and told the rest of us,” Kevin tells Anatomy of a Massacre.

The bomb in Monaghan town centre exploded at 6.58pm. It was in a green Hilman Minx, which had been stolen that afternoon in Portadown.

One theory is that this bomb was placed as a decoy to facilitate the return of the bombers to the north, although another theory suggests that the Dublin bombers stayed the night in the city.

Seven people died in the Monaghan bomb.

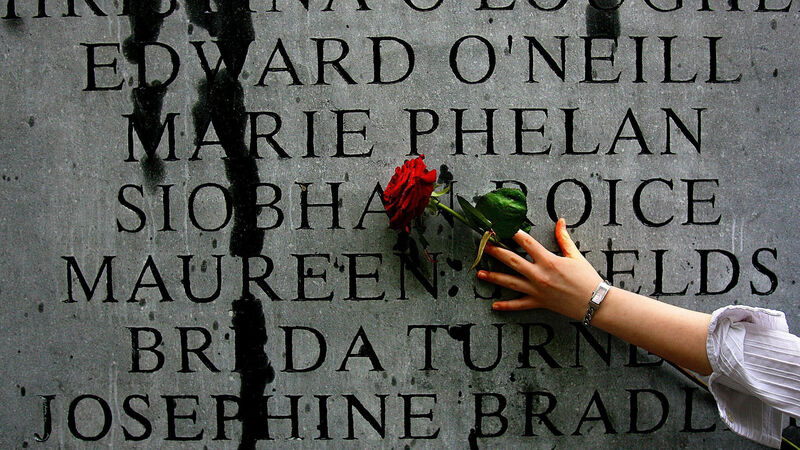

In total, 34 people lost their lives and hundreds were injured as a result of the four bombs.

The bereavement and trauma that resulted reached wide and down through subsequent generations. Exacerbating it all, and elevating the tragedy to scandal, was the manner in which the crimes were investigated.

There are copious amounts of evidence that a proper investigation was not undertaken.

There is evidence that elements of the British security forces were complicit in effectively launching an attack on the neighbouring sovereign jurisdiction.

For nearly 20 years after the bombings, there was little effort at official level to find out what happened. From a political standpoint, the dead, injured, and bereaved were treated as collateral damage in the wider scheme of things.

The bombings took place two days after the Ulster Workers’ Strike began in earnest in the North. This was designed to object to and bring down the Sunningdale power sharing agreement.

Loyalist paramilitaries were prominent in the strike, and it is widely believed to have provided the backdrop to the bombings.

Pretty soon after the event, British army intelligence identified two loyalist groups as being responsible — one from Belfast, the other from mid Ulster.

The latter was part of what has come to be known as the Glennane gang — a notorious outfit that murdered dozens of innocent Catholics, sometimes with collusion from security forces.

In the South, the Provisional IRA, rather than loyalists were considered the greater threat to stability. The Provos stated aim was to violently overthrow the southern Government and install a socialist, 32-county entity.

While such a prospect seemed fanciful to many, the Government took it so seriously that sometimes it appeared as if paranoia was setting it.

Four days after the bombing, then taoiseach Liam Cosgrave addressed the Dáil about the tragedy.

He rhetorically asked what do men of violence hope to gain.

To them, I would say that the only unity they are capable of creating is the unity, in opposition, of all decent men and women to their values and methods.

The men of violence he appeared to be referencing here were of the Provisional IRA.

In his recently published book on the bombings and its aftermath, retired senior Garda John O’Brien comments on Cosgrave’s reference: “The taoiseach’s use of the word ‘unity’ may have conveyed a mindset that the IRA were involved [with the bombing], or at least vicariously. Was he thinking only of the IRA?”

There is not a scintilla of evidence that the Provos had anything to do with it. In any event, the criminal investigation didn’t go anywhere.

The forensic evidence gathered by An Garda Síochána was minimal. The force was not, in any event, yet equipped to properly deal with forensic evidence.

Apart from that, they had some hearsay to go on and some eyewitness evidence from survivors at the various sites. The generally accepted theory is that the bombs were prepared north of the border and driven south.

In this respect, any successful investigation would have to be a joint operation. There does not appear to have been great enthusiasm on either side to conduct a thorough investigation. By August 7, less than three months after the bombings, the Garda file on the matter was closed.

In an atrocity such as this, it would be expected that there would be huge political will to drive on efforts to catch the perpetrators. Yet, the opposite appears to have been the case.

John O’Brien’s book, The Great Deception, puts major emphasis on two meetings between senior figures in the respective governments.

On September 11, 1974, a meeting in London was held between prime minister Harold Wilson, Mr Cosgrave, ministers, and officials from both sides. The minutes prepared by the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs reference Mr Wilson talking about internment of various loyalists, including “the perpetrators of the Dublin bomb outrages … but it was impossible to get evidence to try them in open court.”

So the British had identified prime suspects, had them in custody, and had already determined it was impossible to charge them.

The Irish were given this information, which could go a long way to solving the case, but did nothing about it.

At a meeting in Dublin just over two months later on November 21, similar information was provided.

“He [the prime minister] emphasized again that the people who had bombed Dublin were now interned, and that this was the only way which they could be dealt with because the sort of evidence against them would not stand up in court.

They were certain they had the right people

Interestingly, this meeting occurred on the same day as the Birmingham bombings, in which the Provos killed 21 people and injured 182 others. Were the leading members of the Government distracted by the Provos showing their capacity again?

Did they somewhere, perhaps subconsciously, relegate the plight of the dead and injured at home because of what they perceived as the bigger picture.

John O’Brien writes of the importance of what was imparted at the two meetings.

“This information was critical, crucial, and pertinent to the discovery of the culprits and never actioned.”

Garrett Fitzgerald attended both meetings in his capacity as minister for foreign affairs. Much later, he would tell an Oireachtas subcommittee that it was not the Government’s remit to intervene in the activities of the police at the time in matters such as the bombings.

By any standards, that was an extraordinary position to take. The worst atrocity had taken place in the South since the Irish Civil War, yet senior ministers didn’t want to do anything that might assist bringing the perpetrators to justice. Other ministers from the time gave similar explanations.

O’Brien is not convinced, declaring himself “amazed” at suggestions that “they were concerned to operate within clear protocols of demarcation and boundaries, and they were Jesuitically avoiding getting close to Garda investigations. Nonsense!”

O’Brien also points out that a Cabinet subcommittee on security existed at the time, consisting of the then taoiseach, then tánaiste, and ministers for defence and justice.

“Can anyone seriously believe that this subcommittee did not discuss the car bombings? Can we believe that they were not told of the British admissions? No minutes exist of its deliberations. This group was formed to deal specifically with matters of national security, and yet no footprint of its deliberations exist.”

The most plausible explanation is that the Dublin Government did not pursue the matter, because its sole focus was on the Provos.

On the British, side there was no interest either because those in government suspected — and may even have known — that there had been collusion between the security services and the bombers.

As a result, two democratic governments wantonly ignored a terrible crime that visited intergenerational trauma on dozens of innocent families in the name of expediency.

Nearly 20 years after the bombing, an ITV documentary, Hidden Hand, exposed some of the serious failings around the event and its investigation.

Then, in 1997, Bertie Ahern became taoiseach. He had been in Dublin on the day in question, working as an accountant in the Mater Hospital, and had gone down to the city centre when word came through.

“One of the first things I did when I became taoiseach was I got the file,” he says in the film.

“I didn’t know till then that the Garda file was closed on the August weekend [of 1974].”

In 2000, a commission of inquiry was set up under retired judge Liam Hamilton — but he had to step down because of ill health.

He was replaced by his colleague Henry Barron. The Barron Commission reported in 2003.

He established much of the facts that had been swirling around the scandal over the preceding decades, including the possibility of collusion and the lack of pursuit of an investigation.

Crucially, he also indicted the Government of the day which, he ruled, “failed to show the concern expected of it.”

He did note that he was looking at the issue with the knowledge of 2003 rather than 1974, but he went on: “The Government of the day showed little interest in the bombings. When information was given to them, suggesting that the British authorities had intelligence naming the bombers, this was not followed up. Any follow-up was limited to complaints by the minister for foreign affairs that those involved had been released from internment.”

By the early 2000s, the attitude in Dublin has changed completely and answers were sought. However, the British position remained steadfast and that has persisted until today.

Central to that position is a refusal to hand over vital documents, which would illustrate the intelligence that was amassed about the event and, quite possibly, indicate the extent and specifics of collusion with loyalist paramilitaries.

The co-ordinator of Justice for the Forgotten, a group of survivors and relatives of the bereaved, Margaret Urwin, says that their hope of any closure rests on two reports.

“There is an investigation ongoing for several years with the police ombudsman for Northern Ireland,” she says.

“They have received the co-operation of the gardaí in relation to Dublin and Monaghan.

There is Operation Denton, which is investigating former RUC people, but does not extent to the British army

“We have been told that will be published before the end of the year.”

The hope of the truth emerging at this stage, however, is remote without full co-operation from the British government.

Some 50 years on from a terrible tragedy, the scandal that informed the subsequent investigation has never been fully resolved.

- The Great Deception – Dublin and Monaghan car bombings by John O’Brien is available at jaobrien.ie.

- May-17-74: Anatomy of a Massacre will be screened at selected cinemas from next week.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates