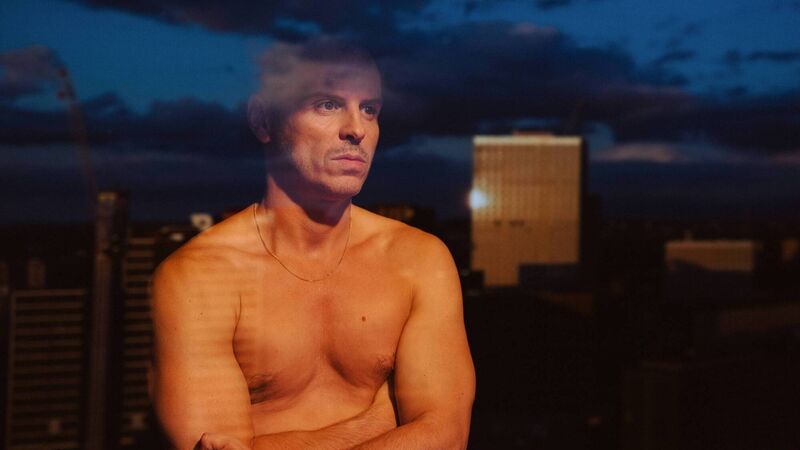

All of Us Strangers: A film about longing, love, loneliness, and the solace of 80s pop music

Andrew Scott in All Of Us Strangers. Pictures: Chris Harris, courtesy of Searchlight Pictures.

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBEWHEN Andrew Haigh was shooting his new film, All of Us Strangers, in his parents’ old house in Croydon, something strange began to happen.

“I started getting eczema again, and I’d not had eczema since I was a kid,” says the director, who is now 50.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

Keep up with stories of the day with our lunchtime news wrap and important breaking news alerts.

Select your favourite newsletters and get the best of Irish Examiner delivered to your inbox

Tuesday, February 10, 2026 - 10:00 AM

Tuesday, February 10, 2026 - 12:00 PM

Monday, February 9, 2026 - 5:00 PM

© Examiner Echo Group Limited