Una Lynskey cold case review may raise more questions for gardaí than deliver answers

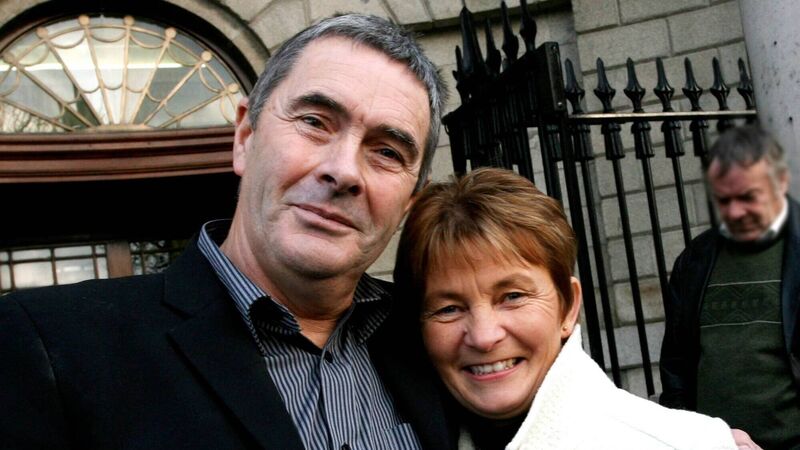

Martin Conmey with his wife, Ann, after his conviction for the manslaughter of Una Lynskey was quashed by the Court of Criminal Appeal. Picture: CourtPix

On Thursday, An Garda Síochána held a press conference, timed to coincide with the anniversary of Una Lynskey’s disappearance on October 12, 1971.

The gardaí’s Serious Crime Review Team is conducting what it calls “a review” into the investigation of Una’s murder. It is also reviewing the investigation into the violent revenge killing of Marty Kerrigan by Ms Lynskey’s two brothers and a cousin.