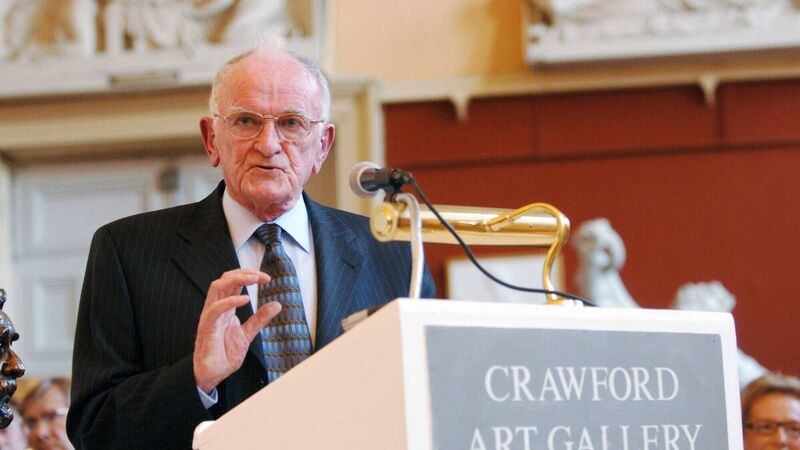

John A Murphy: One of Ireland's foremost public intellectuals

While best known to the public for his roles outside academia, John A. was first and foremost a UCC man

Professor John A. Murphy (known throughout Ireland simply as ‘John A,’ so wide was his renown at its greatest extent) was arguably Ireland’s best-known historian for most of the 1970s and 80s, and one of its most widely-discussed public intellectuals. A native of Macroom, he made the short journey to Cork city when matriculating in University College Cork in October 1945, and save for short periods abroad while on academic sabbatical he remained a proud resident of the city for the remainder of his days.

He gave evidence of his outstanding intellectual ability at Macroom’s De La Salle secondary school, and was an active member (and sometime president) of its past pupils' union for many years. Awarded one of only three Cork County Council scholarships available in 1945, he graduated three years later with a first-class degree in History and Latin, and first place in the order of merit. A teaching career beckoned, and now equipped with both HDip and MA, he took up a position at the diocesan seminary in Farranferris. He spent the following ten years honing his intellect and delivery, while also marrying his college sweet-heart, Aileen (‘Cita’) McCarthy, and becoming a father to the first of what would ultimately number five children (Susan, Clíona, Brian, Hugh and Eileen). Head-hunted shortly before his death by James Hogan, the long-standing Professor of History in UCC, he was appointed Assistant in Irish History in 1960, to a new Lectureship in the subject in 1968, and to the Professorship in October 1971.