From Shannon to Dallas: President John F. Kennedy's final journey

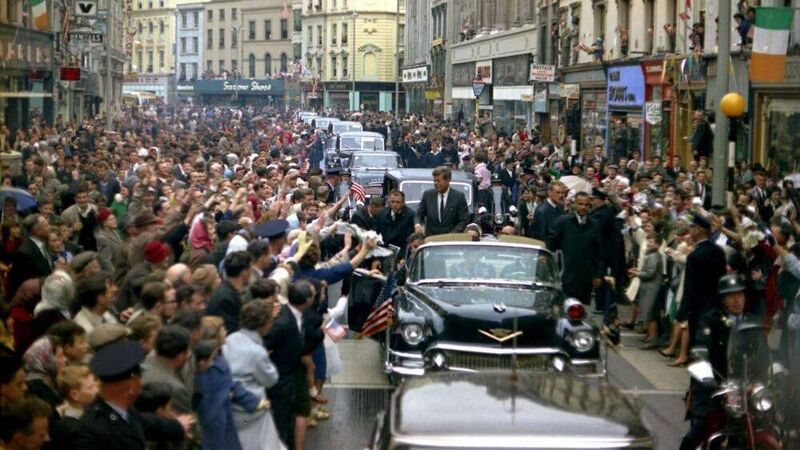

President John F. Kennedy's Motorcade through Cork in June 1963

THE distance from Shannon Airport to Dallas, Texas, is 7,045km. It took the 35th president of the United States 146 days to make this journey, although he took a rather circuitous route.