Stolen identity: The phone call that rewrote a Bessborough survivor's life

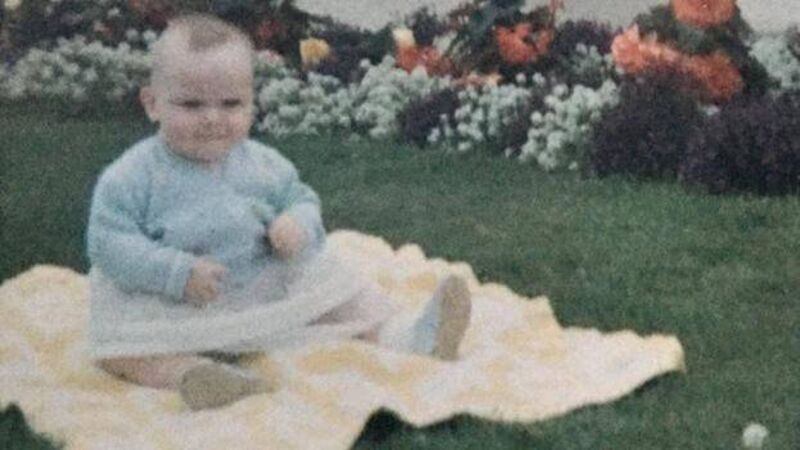

Jean Dunne as a baby. Little did she know that a conversation she would have at the age of 50 would change her life forever.

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBEJean Dunne* was born in Bessborough mother and baby home in the late 1960s. Two decades after she met her birth mother, she got a phone call at the age of 50 that changed everything she thought she knew about herself.

Here, she writes about stolen identity, lost time and living with the relics born of fear, shame and ostracisation.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

Keep up with stories of the day with our lunchtime news wrap and important breaking news alerts.

Select your favourite newsletters and get the best of Irish Examiner delivered to your inbox

Tuesday, February 10, 2026 - 9:00 PM

Tuesday, February 10, 2026 - 12:00 PM

Tuesday, February 10, 2026 - 8:00 PM

© Examiner Echo Group Limited