Our New Lives: Major cultural shifts to our lives ushered in by pandemic unknowns

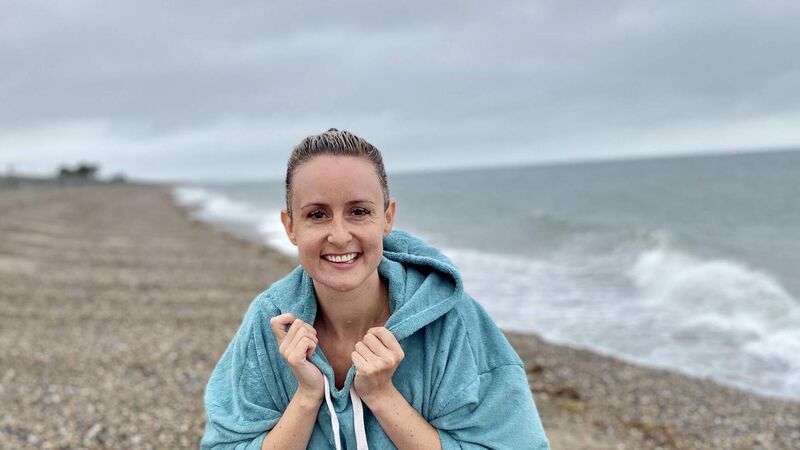

The sea became an anchor for Lisa Collins when the pandemic hit.

The pandemic changed our lives in more ways than just forcing us to work from home and use Zoom. Some of the changes ushered in were major cultural shifts and others were lifestyle changes.

With the murder of George Floyd in May, by a white police officer in America, the Black Lives Matter movement gained a far bigger foothold.