Dutch woman ruled out as Gardaí continue to investigate birth and death of Baby John

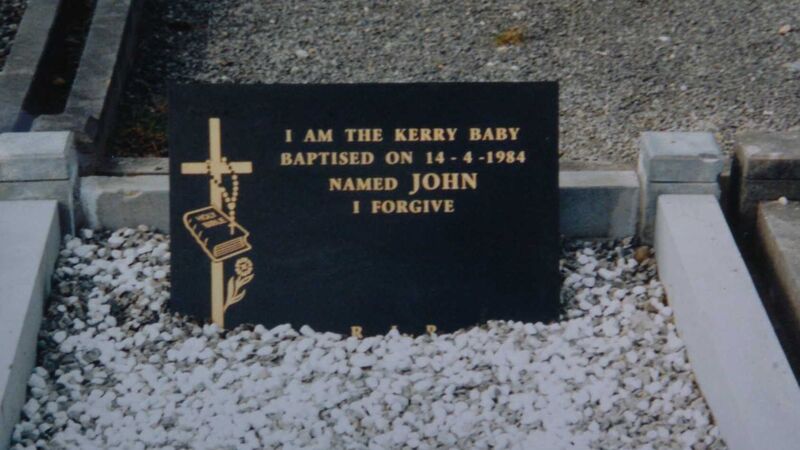

The 'Kerry Baby' grave in Cahirciveen, County Kerry. Picture: Don MacMonagle

'I am the Kerry Baby'.

Five words inscribed on a gravestone, remembering a little boy who didn't live long enough to speak his first words. From the date he was baptized on April 14, 1984, and named 'John', nobody has ever discovered who he is.