Spotlight: ‘We will never stop looking for our loved ones’

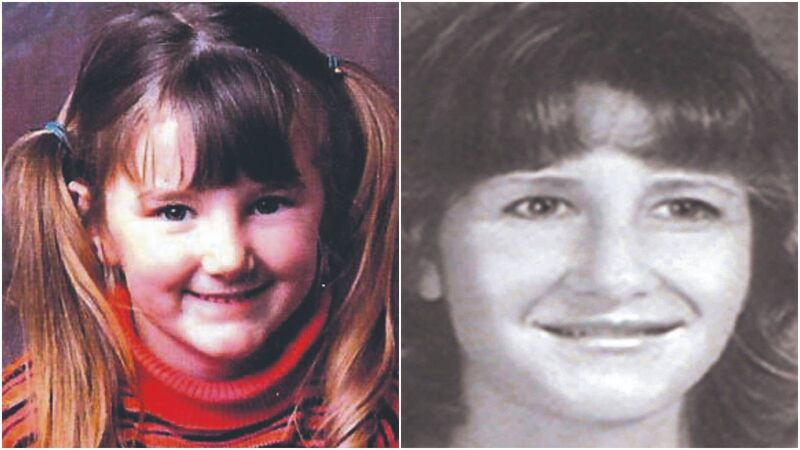

An image of Mary Boyle shortly before she went missing on March 18, 1977. An age progression image issued by An Garda Síochána showing how Mary Boyle may look today

At around 2pm, a little girl was sitting by a fire in her grandparents’ house in rural Donegal just before lunch.

The lively six-year-old suddenly motioned her mother over to her.