Colin Sheridan: Demonised by the Church, it's no wonder jazz caught on in Ireland

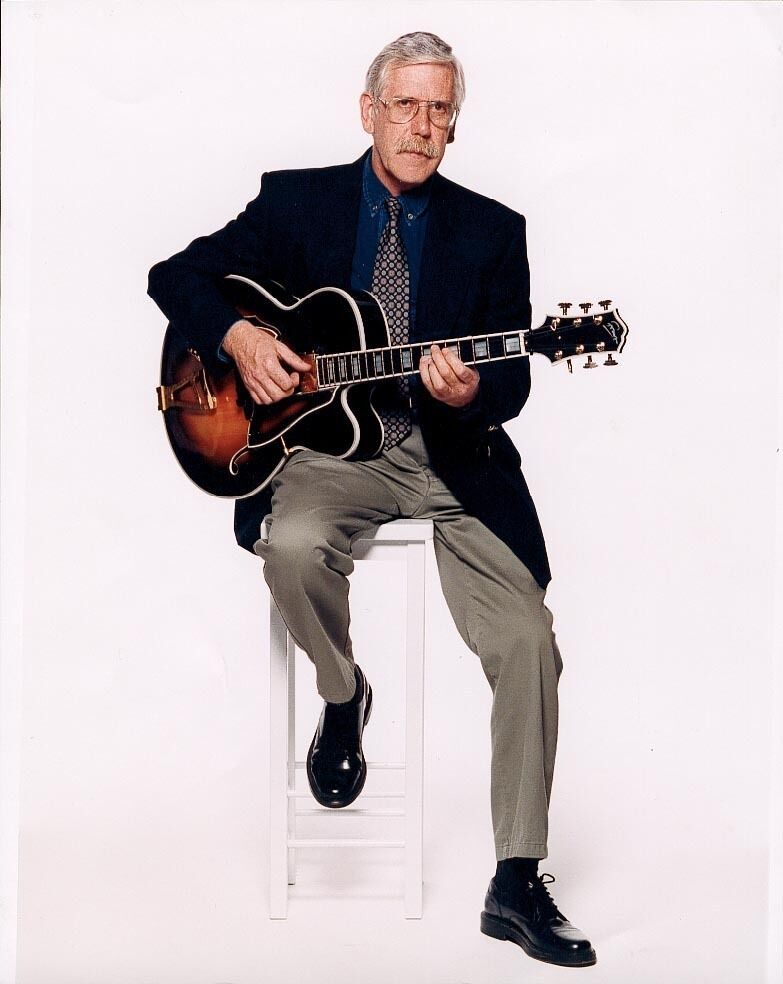

Dubliner Louis Stewart may not be well known to music lovers now, but, in his heyday he was regarded as one of the finest jazz musicians in the world.

"Hot can be cool & cool can be hot & each can be both. But hot or cool man, jazz is jazz." — Louis Armstrong

If history has taught us anything in this country, it is that if the Irish Catholic Church was against something in the first half of the 20th century, you should probably do it.

In the early 1930s, self-appointed spokesman for the Gaelic League Fr Peter Conefey decried jazz music as "borrowed from the African savages by the anti-God movement, with the object of destroying morals and religion".

If there was ever a statement to inspire young men and women to dance, this was surely it. His declaration of war was part of a broader smear campaign against jazz in Ireland, a style of music that the church posited as malevolent, sexualising and pagan. Talk about a call to musical arms.

On New Years Day 1934, Fr Conefey led a march through Mohill, Co Leitrim, where over 3,000 people turned up to protest this "fruitful source of scandal and ruin".

Then president of Dáil Éireann Éamon de Valera even sent a message of support to the campaign, which argued that jazz was “abominable” music that originated in central Africa and was exported to the West by “a gang of wealthy Bolshevists in the USSR to strike at church civilisation throughout the world”.

Publicly, Dev agreed, privately I cannot help wonder did he dispatch his representative to Leitrim with stern instructions, before closing the door and happily toe-tapping to Django Reinhardt.

The genre was the subject of Dáil debate and was a catalyst for the draconian Dance Halls Act of 1935 and was expelled from the airwaves of Radio Éireann.

The anti-jazz movement was surely one of the formative ‘Down With This Sort Of Thing’ episodes in contemporary Irish history. With that kind of opposition, it could not but catch on.

It took a while, however. With Conefey and others initially successful in their campaign of spiritual scaremongering, jazz may have disappeared from the airwaves, but much like bootleg liquor in prohibition America, it could be found in dark corners if one were willing to look.

Throughout the 1940s, it developed as a popular youth subculture, but with the shadow of the church still looming large, the music remained homeless, hopping as it did from place to place.

By the 1950s, jazz had found an altar in the Green Lounge on St Stephen’s Green. By the end of the decade, as the church’s influence began to wane, you could listen to live jazz in Dublin every night of the week.

As its popularity grew, so did the quality of Irish jazz musicians, even if fame eluded its brightest stars. Dubliner Louis Stewart may not be well known to music lovers now, but, in his heyday he was regarded as one of the finest jazz musicians in the world.

Stewart regularly toured and recorded with luminaries Benny Goodman, Tubby Hayes, Ronnie Scott and George Shearing, while his solo album is regarded by many as a jazz masterpiece, the equal of any of his peers.

In the 1960s, Stewart regularly gigged at the Martello Room, a bespoke venue on the roof of the Intercontinental Hotel (later Jurys) in Ballsbridge.

The town of Ashbourne, Co Meath, became the rebel capital of jazz for a while, as Stewart performed at the Fox Inn — sometimes as often as five nights a week with his own band — as well as visiting musicians. The zenith of those cameos was a weeklong residency with legendary American saxophonist Lee Konitz.

Still, as Stewart’s star in the wider jazz world grew, he remained an anonymous presence in Ireland. While the rock and punk scene grew to international acclaim, Stewart went quietly about his business.

Up until about 10 years ago, you could regularly catch him playing at JJ Smyths on Aungier Street, jamming in front of 30-40 people, all for the price of a tenner.

Like Joyce and Beckett before him, Stewart fulfilled the most Irish of prophecies of being regarded as a genius abroad, only to be greeted with mild indifference at home.

Unsurprisingly, Stewart played at the very first Cork Jazz Festival in 1978, and returned many, many times, both as a solo performer and in support of others.

Quite fitting that the first festival in 1978 was a happy accident, established, as it was by Jim Mountjoy, the marketing manager of the Metropole Hotel at the time, who reacted to the sudden cancellation of a bridge club booking (and the first October bank holiday weekend), by hastily convening a jazz festival.

How apt that a gathering of practitioners of the most improvisational of musical genres was born from the need to fill a room.