UCC study finds never-before-seen preservation of animal tissue in volcanic rock

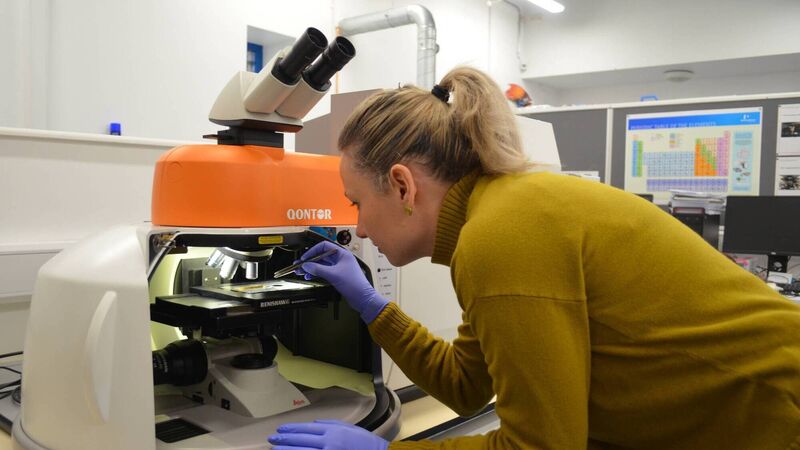

The international team, led by UCC's Dr Valentina Rossi (pictured) showed that the feathers of an ancient vulture were preserved in microscopic 'feather pigment structures'. Picture: Dirleane Ottonelli

A groundbreaking new discovery in the study of a 30,000-year-old vulture fossil, led by University College Cork (UCC) research, has shown that volcanic rock can preserve tiny elements of animal tissue.

In studying the ancient vulture, first discovered by a farmer in 1889 near Rome, the researchers were able to show that the feathers of the remarkably well-preserved animal were preserved in microscopic “feather pigment structures”.