State Papers: 'Firm view' £40m sought to save Irish Steel in Cork 'could be put to better use'

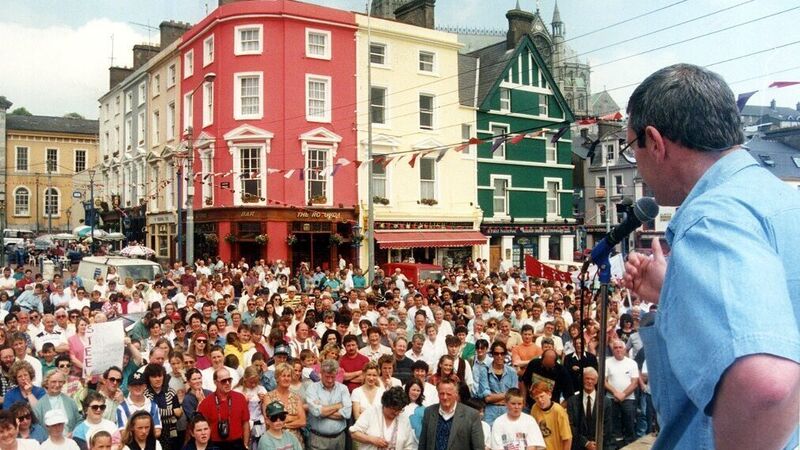

Irish Steel worker and Siptu member Jim O'Leary addressing a protest rally in Cobh Co Cork on Sunday, July 17, 1994. Picture: Ted McCarthy/Irish Examiner Archive

The Department of Enterprise and Employment held “the firm view” that £40m sought by Irish Steel in government supports in 1994 to save the troubled Cork-based steel manufacturing plant “could be put to better use for employment creation".

State papers released under the 30-year rule show the Minister for Enterprise and Employment, Ruairí Quinn, remained unconvinced by a survival plan proposed by the company to save 350 jobs at the facility in Haulbowline in Cork Harbour.