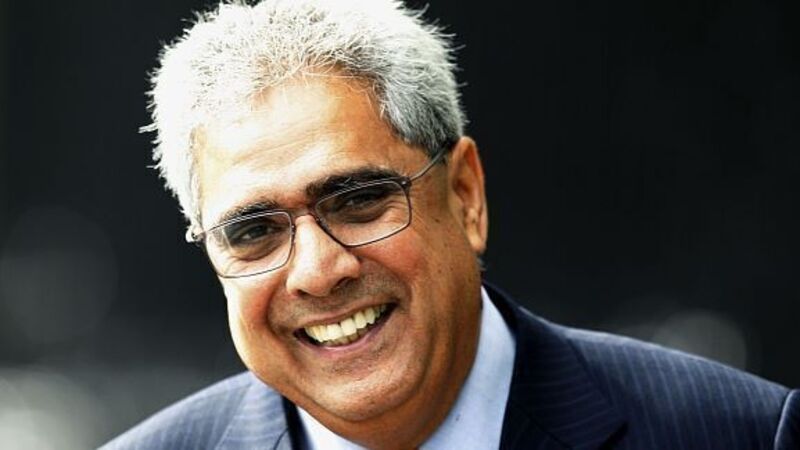

EX-IMF chief Ajai Chopra: ECB 'only grudgingly provided' support to Ireland's banks

European banking chiefs overstepped their role by giving Ireland an ultimatum ahead of its punishing international bailout, a former International Monetary Fund (IMF) chief has said.

In a scathing attack on both Frankfurt and Brussels, Ajai Chopra, ex-deputy director of the IMF, said Europe worsened the economic crisis at the time and lumped more debt on Irish shoulders.