Two-year journey took 30 years to tell

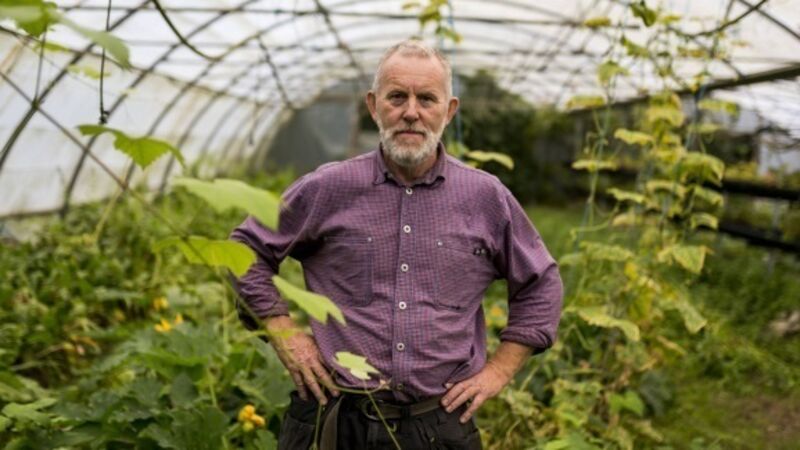

West Cork organic farmer, John Devoy, tells about the perils and pleasures of his epic, 33,000km solo cycle between 1985 and 1987, and why he has only written about it now.

When John Devoy set off from Cork to cycle 33,000km solo, from Ireland to Capetown, via the Arctic Circle and the Middle East, his first stop was in Lismore, to meet renowned, slow-journeying travel writer, Dervla Murphy.