The gory stories of our beloved, bloody nursery rhymes

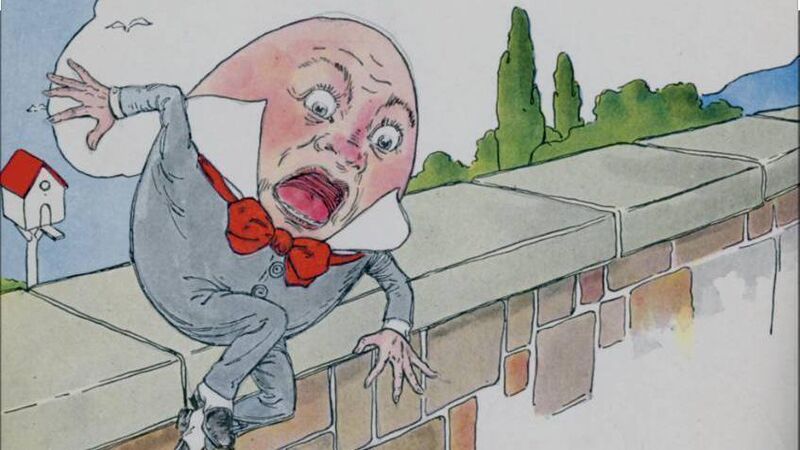

Humpty Dumpty: had a great fall, attempts to reasemble him ultimately proved unsuccessful

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBELast year, a survey by the IB4UD blog included “Mary had a Little Lamb” and “Baa, Baa, Black Sheep” among Ireland’s Top 3 nursery rhymes. But it was “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” — “mecca of all Irish nursery rhymes” — that achieved the top spot.

These days, nursery rhymes can be found in countries all over the world — from Bolivia to India, Kenya to the USA. But until a couple of hundred years ago, such songs, passed down by word of mouth since at least the 14th century, were known simply as ‘rhymes’, ‘lullabies’ or ‘ditties’ — and they were not written especially for children.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

The best food, health, entertainment and lifestyle content from the Irish Examiner, direct to your inbox.

Newsletter

The best food, health, entertainment and lifestyle content from the Irish Examiner, direct to your inbox.

© Examiner Echo Group Limited