Finding my grandfather's grave: a journey, a legacy, and peace

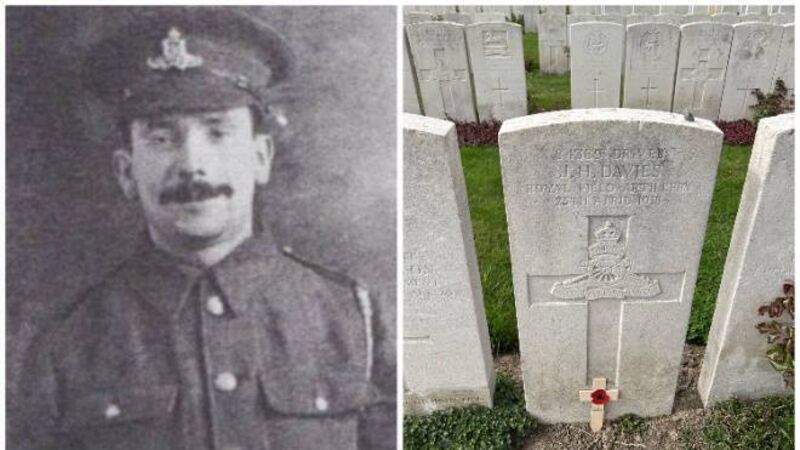

JH Davies - whose grave his granddaughter Roz Crowley and family travelled to Ypres in Belgium to see.

Every year on Remembrance Sunday, the day of commemoration for those who died in the world wars, my mother would go quiet. One year I remember her standing beside me scrubbing potatoes at the kitchen sink, her lip quivering. There may have been tears, but she didn’t shed them, not wanting to upset us.

Perhaps there wasn’t much to tell, just the memory of waving goodbye to her father from the door of their house in Southwark, London. A stark memory for a six-year-old.