The forgotten Kennedy: JFK's great-grandmother Bridget Murphy's roots lie in New Ross

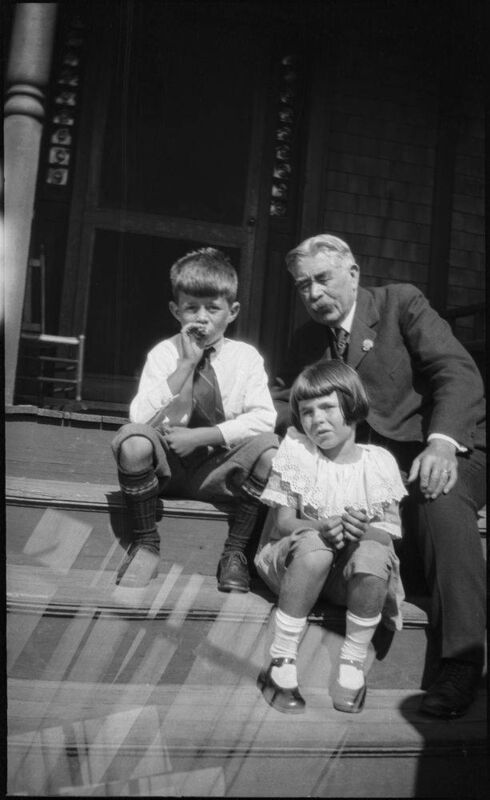

Joseph Patrick Kennedy with his sisters Loretta and Margaret, c. 1902. Picture: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

The first time I heard the name Bridget Murphy, I was in the dirt-paved parking area of the Kennedy Homestead, in Dunganstown, south of New Ross, the birthplace of Patrick Kennedy, great-grandfather to John F Kennedy, Robert F Kennedy and their clan.

I learned that day, in 2006, that Bridget Murphy had left Ireland around the same time as Patrick, whom she married in Boston in 1949, and had grown up on a farm a few miles away, in Cloonagh. All that remained was a patch of grass, trees and some rubble, not tourist-attraction ‘Homestead’ for the matriarch of America’s royal family.

Much of the story focuses on the overlooked life and times of Bridget, who was left widowed with four kids in 1857, when Patrick died of tuberculosis at age 35. She worked, as did most Bridgets (aka Biddies), as a maid.

One reason I was drawn to Bridget’s story was this: my Irish-immigrant grandmother, Bridget Fox, came to America (from Co Galway) and married another Irish immigrant named Patrick Burke. After starting their family (in New Jersey), Patrick died at age 35, leaving my grandmother to raise three kids alone — including my 12-year-old mother. Like Bridget Murphy Kennedy, my grandmother worked as a maid, and later a seamstress. In fact, because the name Bridget was so common among generations of Irish maids in American households, my grandmother changed her name to Della, to avoid the connotation. “She hated the name Bridget,” an uncle would tell me.

Like my grandmother, Bridget Murphy Kennedy faced long odds in a hostile, anti-Irish climate. Yet she managed to work her way out of the pits of domestic service, becoming a hairdresser at a Boston department store just before America’s Civil War (1861-1865), and after the war opened her own small grocery store on Border Street on the immigrant-packed island of East Boston. By the time of her death in 1888, JFK’s widowed great-grandmother owned the grocery store building and rented apartments to incoming Irish immigrants, two of whom married her daughters.

Bridget’s remarkable ascent — from maid to hairdresser to business owner and landlady — has been given short shrift in most books about the Kennedys, and by the Kennedys themselves. When JFK visited his great-grandparents’ home turf of New Ross in 1963, for example, he gave a shoutout to Patrick the barrel maker but not to Bridget the grocer.

“When my great grandfather left here to become a cooper in East Boston, he carried nothing with him except two things: a strong religious faith and a strong desire for liberty,” Kennedy said that day on the New Ross quays.

“I am glad to say that all of his great-grandchildren have valued that inheritance.” He’s not known to have publicly mentioned Bridget, who left from those same quays in her mid-20s (in 1847), travelled first to Liverpool and then boarded a ‘coffin’ ship to make the dangerous Atlantic crossing. One reason Bridget’s story has been overlooked is the persistent male-dominant bias in a family whose men clearly had complicated and imperfect relationships with women.

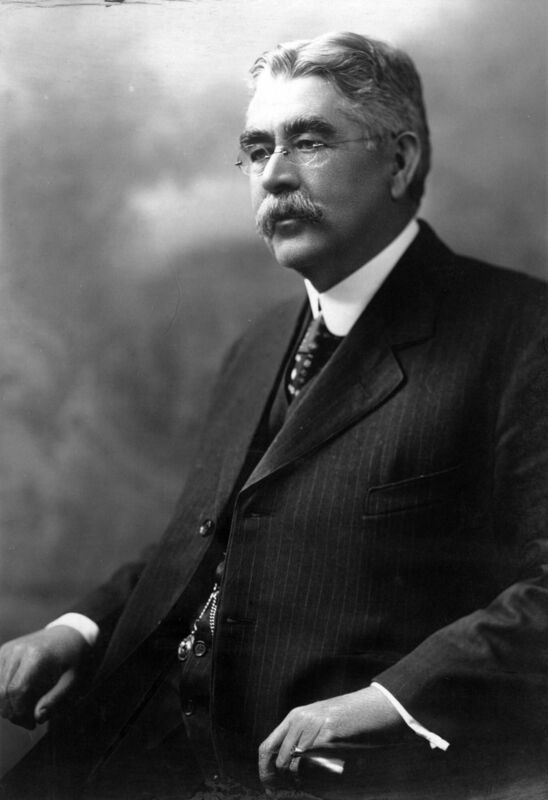

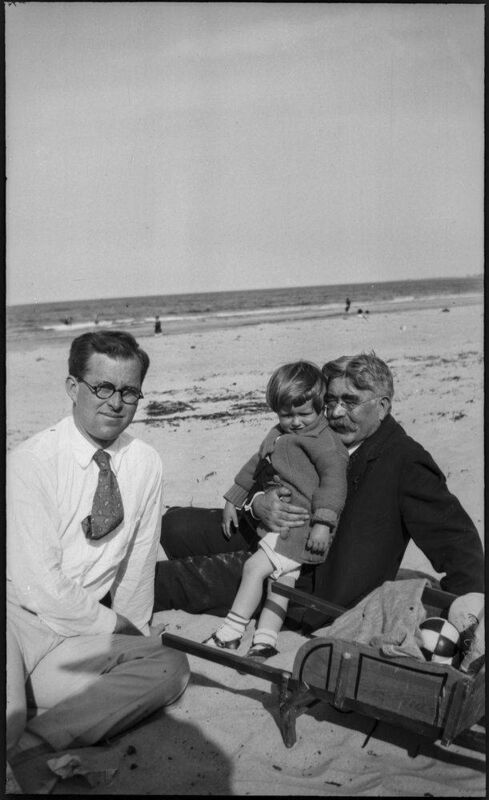

Another reason: Joseph P. Kennedy, father to JFK and RFK, rarely acknowledged his immigrant roots. He couldn’t get far enough away from tales of the auld sod and the Famine echoes. He never knew his grandmother Bridget, barely knew his other Irish grandparents, and felt little connection to his ancestors, the land they’d fled, or the hopes and fears that drove them.

In public life he rarely credited his refugee grandparents nor his up-by-their-bootstraps parents, including Bridget’s lone son, Patrick Joseph (PJ), a saloon keeper who became an influential Boston politician and a wealthy banker, who gave Joe Kennedy his start in the banking business. Joe’s mother, Mary, had intentionally bestowed on him a ‘not-obviously-Irish’ name, and though a few of Joe’s kids were later given ‘Irish-ish’ names, he strove to be fully Americanised.

In turn, America has sustained a lasting fascination with the flawed and fabulous Kennedys, the style and the glamour, the shortcomings and tragedies, the promise of John and Bobby and other lives cut short — including John’s son, John Jr, who died in a plane crash less than 30 miles south of the family’s summer compound at Hyannis Port, less than 70 miles south of the waters that welcomed his great-great-grandparents to America 150 years before.

Yet none of the Kennedys’ accomplishments, nor the fantasia of Camelot, would have occurred without the brave ambition of Bridget, the dramatic and inspirational story of a resilient immigrant maid making her way in a less-than-tolerant America, paving the way. The Kennedy saga is one that started with nothing. Just a poor, hardworking widowed grocer named Bridget and her four fatherless children in an East Boston tenement.

- Neal is taking part in A Festival Of Irish & American History, Culture & Politics from September 8-10. book tickets at kennedysummerschool.ie