Sat, 10 Oct, 2020 - 08:00

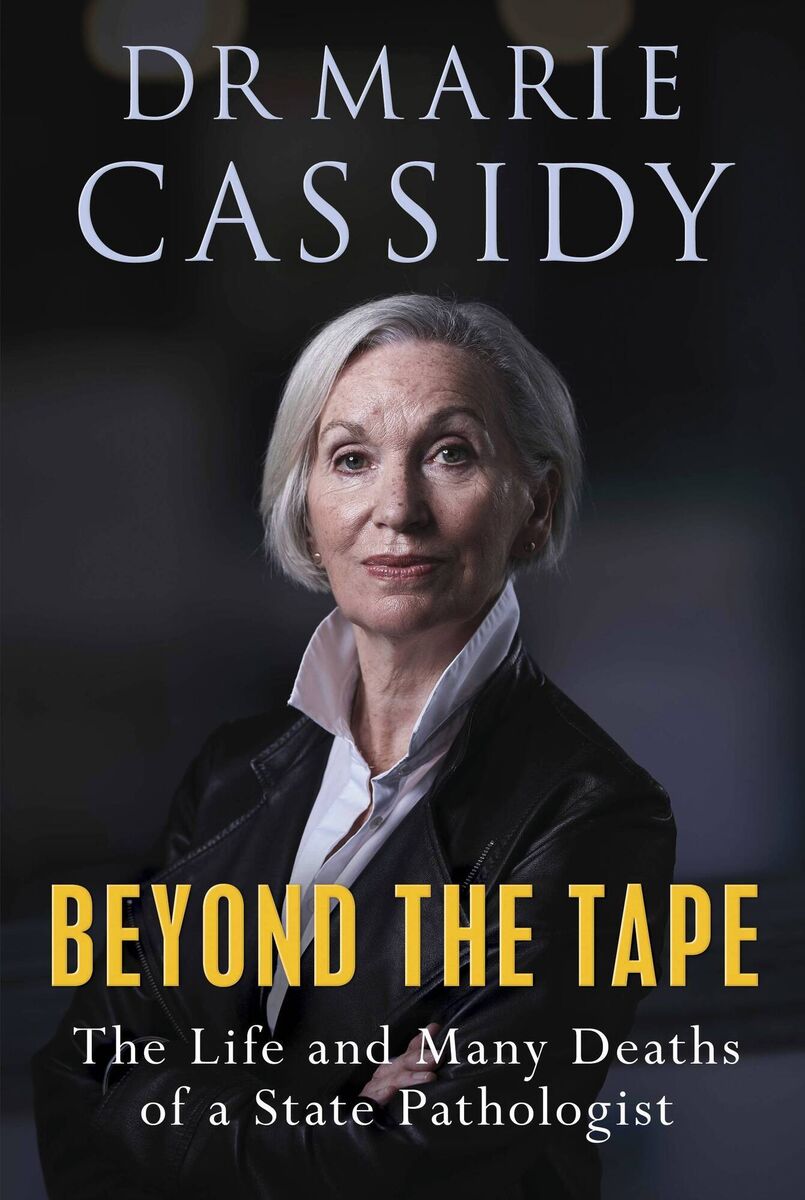

Dr. Marie Cassidy

The case of Manuela Riedo

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Subscribe to access all of the Irish Examiner.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates