Anja Murray: Seagrass meadows and other Irish marine life marvels

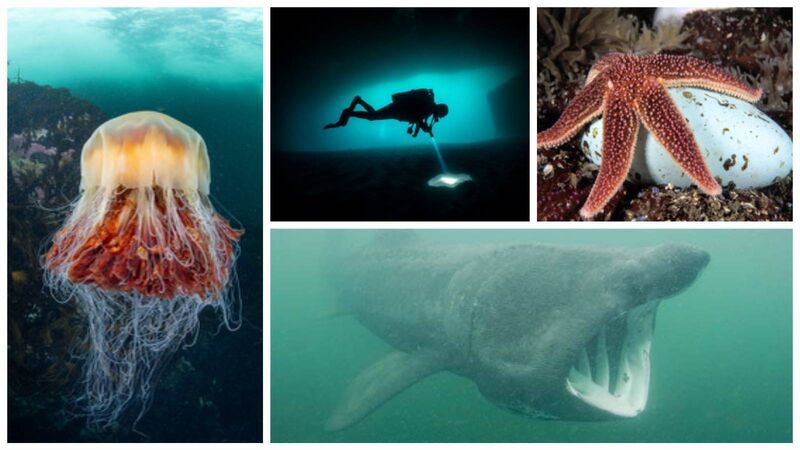

Left to right: Jellyfish, Skellig Michael; Cave diving, Inis Mór; Single starfish and egg; basking shark. Featured in Beneath Irish Seas — The Hidden Wonders of Ireland's Amazing Marine Life, by Nigel Motyer

All around Irish coasts, seagrass grows in shallow waters and brackish estuaries...

Luminous green fronds sway in salt water and shelter a wealth of marine life.