Sky Matters: Find a dark site on a cloudless night — to change your sense of place in the universe

The milky way in Caldera De Taburiente, La Palma Island, Canary Islands.

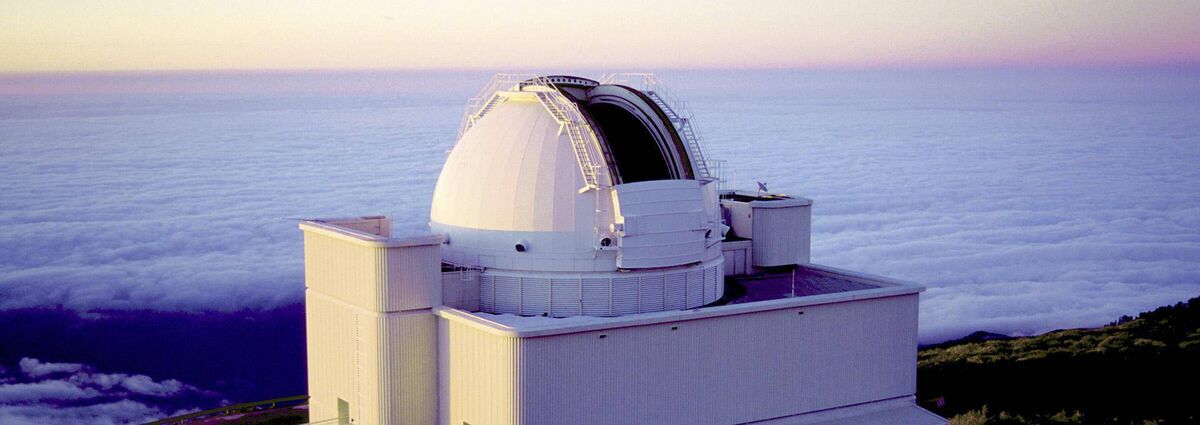

It was a dark February evening. In 1989. Devoid of the lights of civilisation and with only a dim red torch to illuminate the way, I was forced to choose my steps carefully as I ascended the 1.5 kilometre roadway from the astronomers' 'residencia' up to the array of telescopes perched atop the Canary Island of La Palma. The European Northern Observatory, high above the clouds and far from lights, save for the garish glow of distant Tenerife. The following night I was due to start observing.