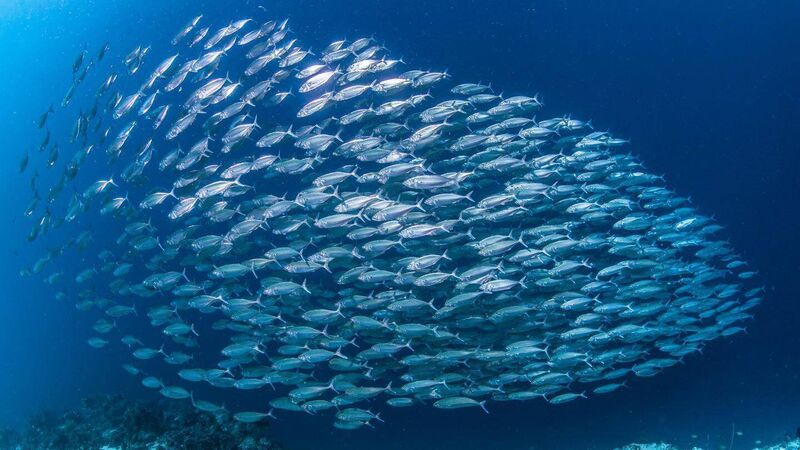

Richard Collins: What's quieter than a fish swimming? A whole school of fish

School of mackerel. Picture: Getty / Johns Hopkins University

The murmuration season has come to an end. Only small starling flocks remain. Our resident Irish ones haven’t far to go to nest. Many of them will have paired in the autumn and remained together through the winter. It’s a different story for the visitors, particularly those from mainland Europe. Their journeys home can be very long indeed. Males usually arrive at their destinations first.

Flocking is a starling thing; these gregarious birds like to breed in loose colonies, nesting birds associating with others when feeding. Needless to say, ‘extra-pair copulations’ occur, but variety is the spice of life and nobody is perfect. In one Belgian study, up to 60% of males had ‘flings’. Later in the summer, bands of newly-fledged teenagers roam the countryside, merging eventually into next winter’s murmurations.