Anja Murray: Why it's vital to banish crayfish plague

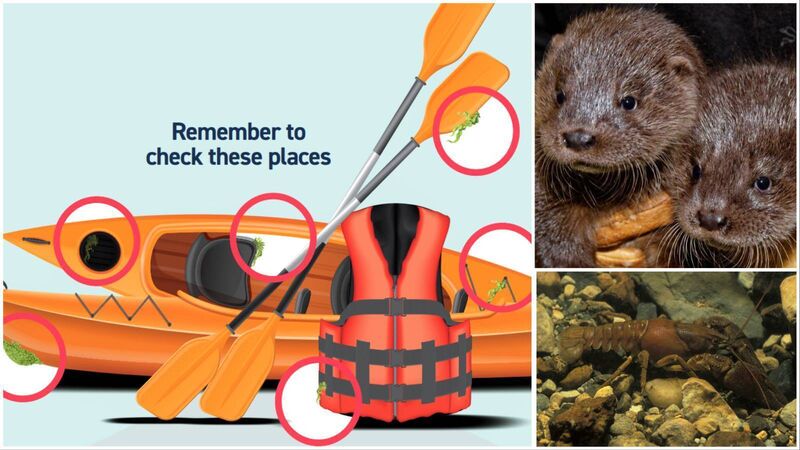

Kayakers, anglers, and other recreational water users are being urged to take precautions across the Munster Blackwater catchment, including thorough cleaning and disinfecting of all boating and other equipment, to stop crayfish plague spreading. Crayfish are a favourite food item for otters.Trout, eel, and perch also eat young crayfish

Crayfish are a funny little animal, more lobster than fish. They are freshwater relatives of the marine lobsters, and like lobsters, Crayfish have a hard outer shell and big front crablike claws.

It is this hard outer shell that means crayfish can only survive in calcium-rich waters, such as where rivers and lakes are underlain by limestone. Calcium is the main component of this outer shell, which they shed and grow afresh throughout their lives — so crayfish don’t fare well in acidic rivers or mountain lakes where calcium is on short supply.

![<p> The International Union for the Conservation of Nature says that “an ecosystem is collapsed when it is virtually certain that its defining biotic [living] or abiotic [non-living] features are lost from all occurrences, and the characteristic native biota are no longer sustained”.</p> <p> The International Union for the Conservation of Nature says that “an ecosystem is collapsed when it is virtually certain that its defining biotic [living] or abiotic [non-living] features are lost from all occurrences, and the characteristic native biota are no longer sustained”.</p>](/cms_media/module_img/9930/4965053_12_augmentedSearch_iStock-1405109268.jpg)