Donal Hickey: What happens to coursed hares when they are released?

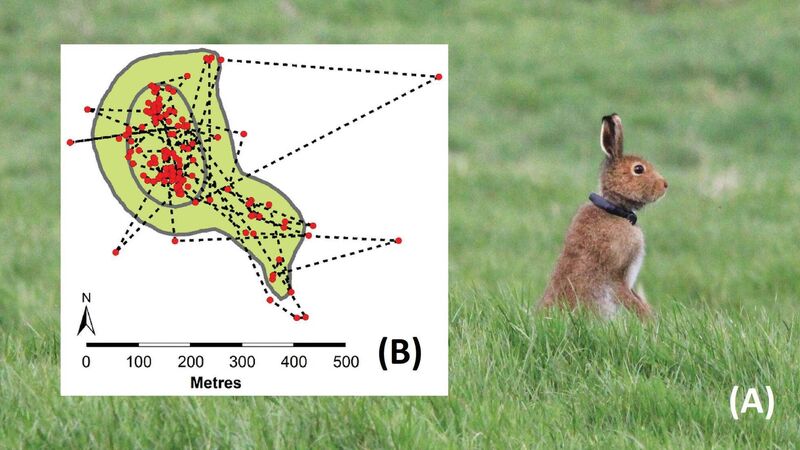

An Irish hare (Lepus timidus hibernicus) wearing a LOTEK Ltd. Litetrack RF60 collar after release back into the wild. The red dots show the hare's GPS locations for one week. In this example, the average step length was 68m/hr, the furthest single movement was 530m with the animal travelling on average 1.7km/24hrs and 11.6km/week. Picture: Neil Reid

Though not as numerous as it was decades ago, the hare continues to be one of our most widespread wild mammals, according to the Irish Wildlife Trust (IWT).

Enclosed hare coursing, even with muzzled greyhounds, continues to be controversial and there are also issues around what happens to hares when they’re returned to the wild after coursing meetings.

The IWT says hares can respond rapidly to habitat changes — adding that, if areas of uncultivated ground for shelter and stock-free pastures are provided, numbers can even increase.

In recent years, 2,900 to 3,700 hares have been caught from the wild by coursing clubs, under Government licence, and held in captivity for up to eight weeks.

A recent study for the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) — which says 99% of hares survive coursing and are allowed back to the wild — aimed to assess survival and behaviour of coursed hares after their release.

Forty hares were tracked using GPS-radio collars for six months in an effort to test the impact of coursing and their movement to a different, often unfamiliar, location. It seems uncoursed hares fared better than those coursed.

Conducted by Dr Neil Reid, a senior science lecturer in Queen’s University Belfast, the study found fewer coursed than uncoursed hares remained near the release site, six months later, with more coursed hares moving on.

This was not because more died, but a combination of coursed hares removing their collars, and radio silence from several coursed hares released to new locations.

Two hares freed shortly before sunset were killed in road traffic collisions during their first night. Releasing hares during daylight, preferably as early as possible, may provide time for animals to settle before darkness, Dr Reid suggested.

He also said improved tracking methods, such as the use of mobile phone, or satellite, communications, mounted on stouter straps attached to hares might be used in future studies.

Separately, wildlife lovers are mourning the passing of Sean Buckley, who opened Coolwood Nature Reserve, near Killarney, County Kerry, in 1993. A man away ahead of his time, I remember him highlighting the plight of dwindling red grouse, in the uplands of Cork and Kerry, more than 40 years ago, when there was far less interest than now in wildlife conservation.

His Killarney reserve featured a large number of animals, some exotic, including lemurs, prairie dogs, monkeys, alpacas; birds of prey like owls and eagles and a large waterfowl collection. Sean closed the facility, five years ago, citing ‘too much red tape’ from the authorities.

He was laid to rest in his native Ballydesmond, County Cork, and deepest sympathy is extended to his family.

![<p> The International Union for the Conservation of Nature says that “an ecosystem is collapsed when it is virtually certain that its defining biotic [living] or abiotic [non-living] features are lost from all occurrences, and the characteristic native biota are no longer sustained”.</p> <p> The International Union for the Conservation of Nature says that “an ecosystem is collapsed when it is virtually certain that its defining biotic [living] or abiotic [non-living] features are lost from all occurrences, and the characteristic native biota are no longer sustained”.</p>](/cms_media/module_img/9930/4965053_12_augmentedSearch_iStock-1405109268.jpg)