Biochar: The ancient Amazon charcoal seen as the next big thing

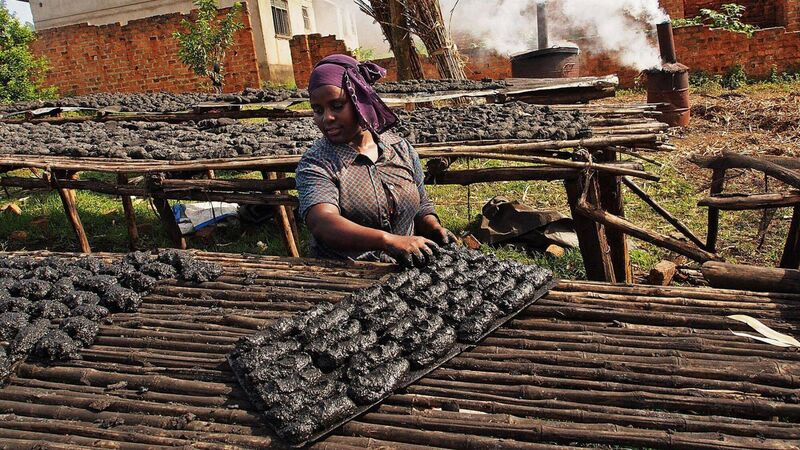

A worker lays out biochar to dry in the sun in Lugazi, Uganda. Picture: Michele Sibiloni/AFP/Getty Images

A type of charcoal first used by Amazonian tribes thousands of years ago is becoming a key component of net-zero goals set by Microsoft Corp., JPMorgan Chase & Co. and other blue chip companies eager to offset their carbon emissions.

Known as biochar, this black substance created by heating biomass and other agricultural waste can store carbon for hundreds of years and improve soil quality at the same time. It’s a “true carbon removal solution at scale,” according to Microsoft, and the tech giant along with BlackRock Inc. and JPMorgan are among those that have bought biochar credits.