Biodiversity or biomonotony: we know what needs to be done, now we just need to do it

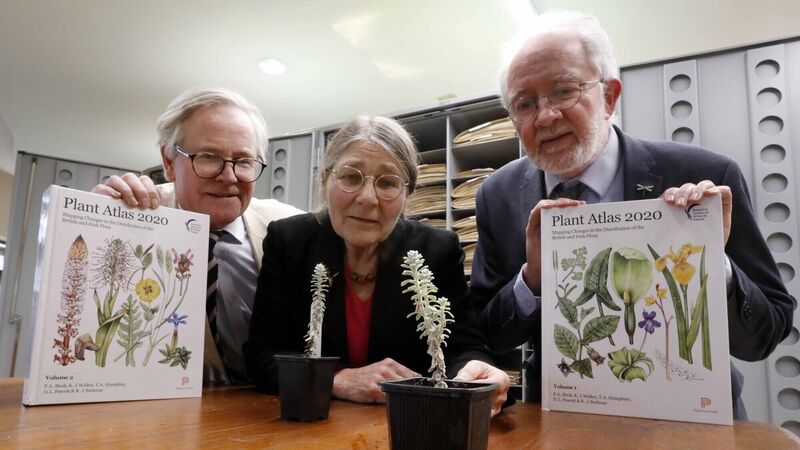

At the official launch of the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland’s (BSBI) ‘Plant Atlas 2020’ at the National Botanic Gardens, Dublin are President of the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland, Micheline Sheehy Skeffington; Minister of State for Heritage and Electoral Reform, Malcolm Noonan TD (right) and Matthew Jebb, director of the National Botanic Gardens. They are looking at Cottonweed Achillea maritima which is down to 11 total plants in Ireland from thousands in 20 years due to coastal erosion. Picture: Mark Stedman

Wild plants grow everywhere, each species endowed with adaptations to thrive in a particular set of conditions. Some plants have evolved to cope with acidic soils, like the sundews and sphagnum mosses that thrive in peat bogs. Others are better suited to alkaline conditions, such as the stunning ‘grass of Parnassus’ — not a grass at all but a delicate wildflower that is specially adapted to grow in wet, chalky terrain, such as the wild shores of calcium-rich lakes. Pioneering marram grass and prickly ‘sea holly’ are two of only a handful of species that can cope with the lack of water and permanent saltiness of sandy shorelines. Completely different conditions prevail in a deciduous woodland, where shade is a limiting factor, so woodland wildflowers emerge in early spring from underground bulbs, giving them a head-start before the canopy overhead shades them out.

Each of the 3,800 or so plant species in Ireland has a unique set of adaptations and preferences, honed over time to fill every available niche. The diversity of plants in any given habitat is also the factor that often enables the whole ecosystems to thrive, as many plants stabilise soil for each other, their root systems growing to differing depths, or providing shelter for each other — some being hardy and others less so. Plants create the conditions that they need to thrive, and having allies in this task is what makes an ecosystem resilient. Moving up the food chain, a diversity of plants provides for a diversity of pollinators and other insect dependants. Each species of bee, moth, butterfly and hoverfly also has its own suite of adaptations and preferences when it comes to feeding on the stems, leaves, flowers, and pollen grains of their particular food plants. The assemblage of wild plants and their impressive physiological adaptations are the basis of everything.