Get ready to join in the new space race

FUTUROLOGISTS predicted space hotels would take in their first guests during the 1980s, a permanent moon base would be completed in the early ’90s and another US flag would be planted in the Martian dust by the turn of the millennium.

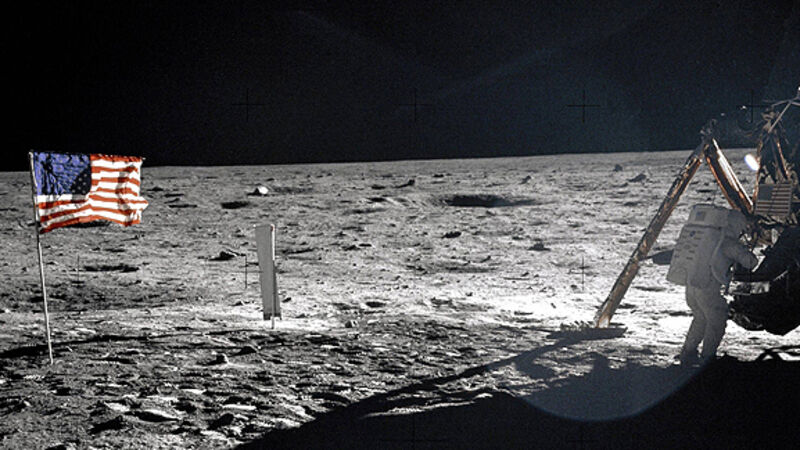

Instead, Earth’s orbit has had a giant flashing ‘Vacant’ sign on it, still awaiting the promised hordes of holidaymakers. The last man on the moon left 40 years ago and the only activity on the lunar landscape since has been performed by a handful of robotic probes.