A murder suspect queuing to buy a loaf of bread in West Cork was the genesis of my book

Business people and concepts vector art

There's often an assumption that works of fiction are based at least in part on actual events that the author has experienced or people that they’ve met, as though writers are more tape recorders than inventors. I strongly suspect that this is very rarely the case.

For me, writing is less diaristic than it is drawing on tiny moments that sparked an emotion. These sparks are then warped into new configurations by the process of fictionalising, rewriting, editing, rewriting again, on and on, until what remains of the original piece is something true to the feeling (hopefully), but completely different from the first synopsis.

There’s a list of tiny moments, fragments of overheard conversations, lyrics from songs, and moments in films that have influenced me, but I think the genesis of Darkrooms was one really formative childhood moment.

It was a summer evening and I was in the back bedroom of my grandparents’ old house in West Cork. I remember sitting on the floor next to two of my younger cousins, the rare treat of my six-years-older sister sitting above on the bed. It was warm, and the room had grown darker around us as we talked. The days were long and the summer endless. My siblings and I didn’t live in Ireland, we only made annual trips there. Two weeks a year spent running in and out of relatives’ unlocked doors, exploring woods and fields and attempting to make friends with farm dogs (a fool’s errand, in my experience, they’re too work-focused). Over here, my sister willingly hung out with me. There was a tinge of Christmas anticipation in the air as we waited for our other cousin, M, who was even older than my sister. M had a flare for the dramatic, she is funny and lively, a wonderful storyteller, all the things that I admire and love in a person.

While we waited, I explained the significance and musical genius of this awesome European band — you’ve probably never heard of them — the Vengaboys. I had recently performed a self-choreographed dance to Boom Boom Boom Boom!! at a school assembly (and I can still perform it to this day).

Halfway through attempting to untangle the true meaning of ‘double boom’, M arrived.

In my memory, the bedroom door flew open and our heads snapped towards her as she announced she had just seen the murder suspect at the shop.

This is the slow-motion part, the bit where my brain struggled to process this new information. I thought it was a joke, and I laughed. I didn’t believe it. We were in a tiny town where most people seemed to know each other. When we sent cards over, we only had to write the recipient’s name and the area they lived in; the postie knew who lived exactly where.

When you are one of the ‘little ones’ and, indeed, a youngest child in general, you’re used to being messed with, teased, and lied to, so I know I suspended belief while M described the murder suspect and how she had found herself, holding a floury loaf of white bread, in the queue behind him.

Some of the questions I had:

1. But how can he just be walking around?

2. Does the cashier have to serve him or can they refuse?

3. Can he be kicked out of places?

4. What did he buy?

I don’t fully remember the answers she gave me, but weirdly it’s the last one that lingers with me the most. The rest I can logically fill in: There was an incredible miscarriage of justice, the cashier probably didn’t have the power as an individual to decide who they would or would not serve, and no, you probably can’t simply kick someone out for having been investigated for murder. It’s that last one, the idea that someone suspected of murder could not only move freely around a community, but also that they would need to eat. He would need to shop, he could stand beside you, holding up two similar boxes of cereal, comparing the ingredients and the quantity and the prices. If you didn’t know who he was, you could spot him, say which type you prefer, exchange a friendly word or two.

Which gave way to the next question:

5. What does he look like?

How will I know if I’m in danger? If this person has infiltrated this community, which had felt so safe and tight-knit to me, what else is out there? Who else is moving through the crowds, taking the stool beside you at a pub to listen to the trad music or waiting next to you for their coffee order?

This small Irish town had been a kind of fairytale for me, coming from the comparatively mean streets of Sunderland, where we would absolutely never leave our doors unlocked and our family dog did double duty as a guard dog, barking her head off whenever someone passed too close to the back of the house. Yet I had never seen a suspected murderer in Sunderland and neither had anyone else I knew. It was an uncanny turning point, whiplash between my very literal dance interpretation of the lyrics to The Vengabus is Coming and the sudden dawning awareness of mortality and violence. That night, I struggled to sleep, suddenly gripped by what ifs.

What if I saw him? What if he saw me? What if he had passed by last night on his own way home from the shops? What if the motion of a little girl twirling and shimmying ridiculously had drawn him to the window, had marked my fate?

Over the years, there have been podcasts and documentaries written about this case, the murder of Sophie Toscan du Plantier in December 1996. The man accused, the one whose identity is flattened in my mind to simply ‘the murderer’, was tried in absentia in France, found guilty, but never served time. He continued living in the area until his death from natural causes in 2024. He had set up a TikTok, actively made videos.

Sophie Toscan du Plantier was a real person who was greatly loved and is very missed to this day. Her story is not part of my novel, but I believe that crime provided a spark for me. That gut-punch emotion hums throughout the narrative.

Whose story is believed, whose word is valued, and how does a community bend itself around rumours of wrongdoing? What if the places we feel safest are capable of harbouring monsters? Who’s watching at your window?

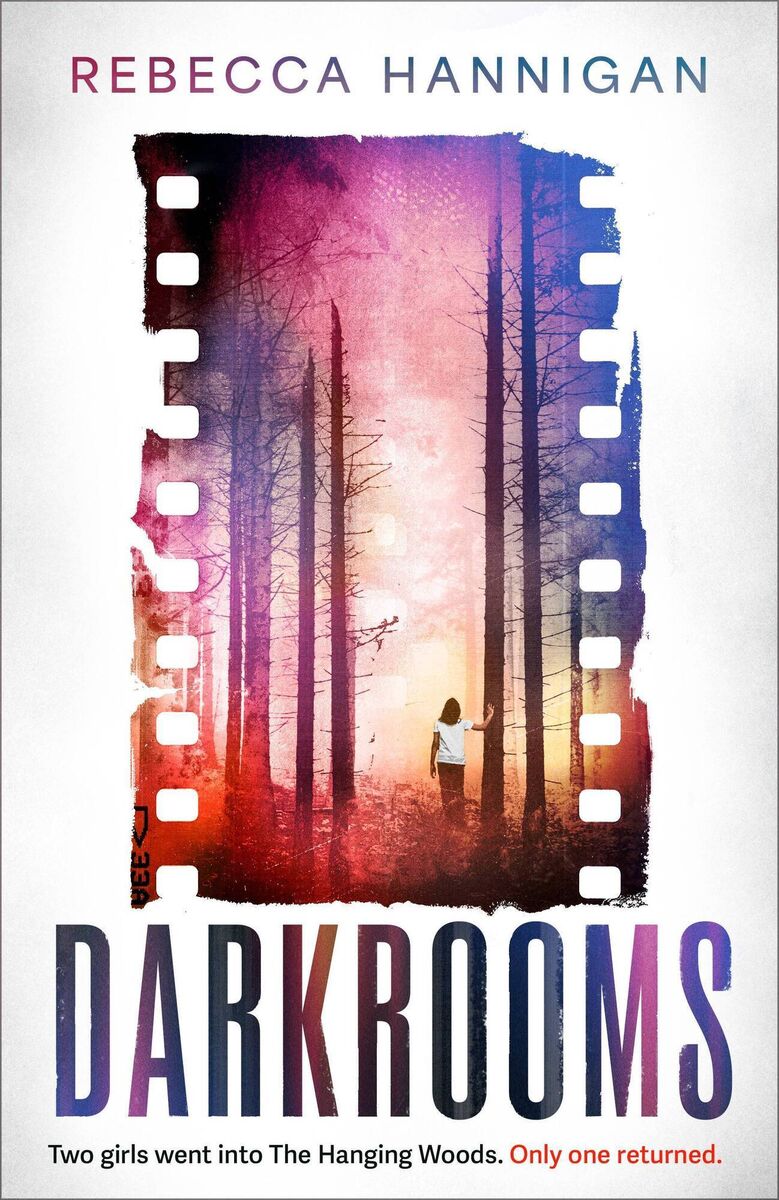

- Darkrooms by Rebecca Hannigan, published by Sphere, €16.99, is out now