Book extract: ‘Turnover tax’ in 1963 was fraught with political risk

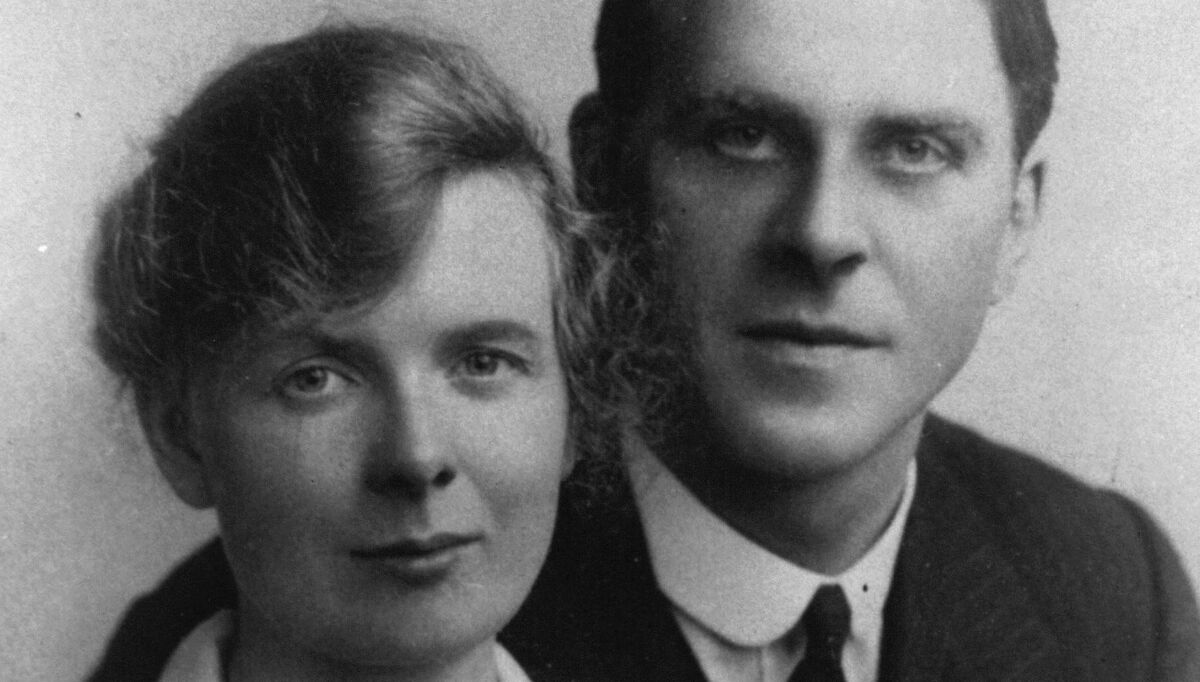

James Ryan on budget day 1957; on his seventh budget in 1963 he proposed a new sales tax of 2.5% on all goods and services, which he christened the ‘turnover tax’. Picture: courtesy of Lensmen photographic archive

- James Ryan and the Development of Independent Ireland, 1892-1970

- Michael Loughman

- Four Courts Press, €24.95

On 23 April 1963, Minister for Finance, Fianna Fáil’s James Ryan, presented his seventh budget in his typical unpretentious fashion.

The minister mumbled and hurried through his speech, as if ‘he did not want anyone to hear it’.

In particular, as one journalist observed, his performance was emblematic of his ability to ‘pack the most deadly wallop into the most innocuous half-articulated phrase’.

Once they had deciphered Ryan’s words, the onlookers learned that he was proposing a new sales tax of 2.5% on all goods and services, which he christened the ‘turnover tax’.

It was the most significant change to the Irish taxation system since independence.

Indeed, in the view of the , it represented the ‘first major departure in taxation procedures in these islands since Pitt introduced income tax’.

Although, if Oliver J Flanagan is to be believed, Ryan bribed him with £3,500. Whatever Sherwin’s reasoning, the bill was approved, and the government survived by a single vote.

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.